It is surely axiomatic that a phenomenon (an appearance, an object) cannot perform any action whatever on its own initiative, as an independent entity. In China this was illustrated by Chuang Tzu in his story of the sow who died while suckling her piglets: the little pigs just left her because their mother was no longer there.

In Europe, even at that early date, the same understanding is expressed by the word animus which ‘animates’ the phenomenal aspect of sentient beings, and this forms the basis of most religious beliefs.

But whereas in the West the ‘animus’ was regarded as personal to each phenomenal object, being the sentience of it, in the East the ‘animus’ was called ‘heart’ or ‘mind’ or ‘consciousness’, and in Buddhism and Vedanta was regarded as impersonal and universal, ‘Buddha-mind’, ‘Prajna’, ‘Atman’, etc.

When this impersonal ‘mind’ comes into manifestation by objectifying itself as subject and object, it becomes identified with each sentient object, and the concept of ‘I’ thereby arises in human beings, whereby the phenomenal world as we know it and live it, appears to be what we call ‘real’.

That, incidentally, is the only ‘reality’ (thing-ness) we can ever know, and to use the term ‘real’

(a thing) for what is not such, for the purely subjective, is an abuse of language.

In this process of personalizing ‘mind’ and thinking of it as ‘I’, we thereby make it, which is subject, into an object, whereas ‘I’ in fact can never be such, for there is nothing objective in ‘I’, which is essentially a direct expression of subjectivity.

This objectivising of pure subjectivity, calling it ‘me’ or calling it ‘mind’, is precisely what constitutes ‘bondage’. It is this concept, called the I-concept or ego or self, which is the supposed bondage from which we all suffer and from which we seek ‘liberation’.

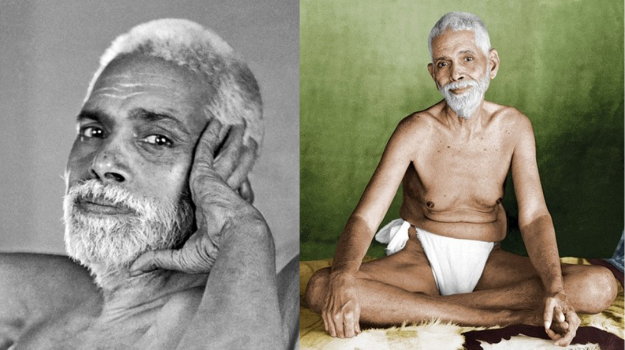

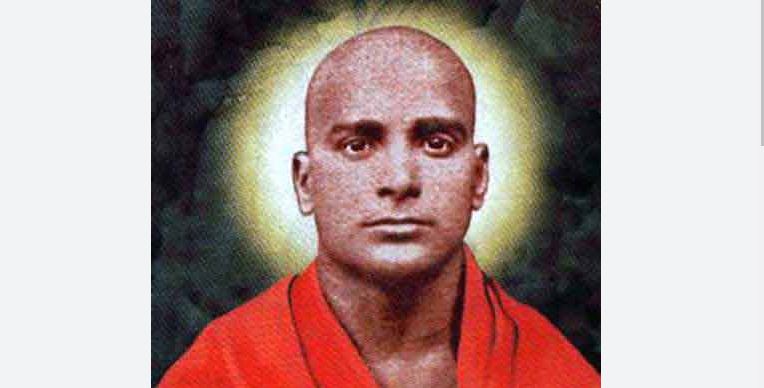

It should be evident, as the Buddha and a hundred other Awakened sages have sought to enable us to understand, that what we are is this ‘animating’ mind as such, which is noumenon, and not the phenomenal object to which it gives sentience.

This does not mean, however, that the phenomenal object has no kind of existence whatever, but that its existence is merely apparent, which is the meaning of the term ‘phenomenon’; that is to say, that it is only an appearance in consciousness, an objecti-visation, without any nature of its own, being entirely dependent on the mind that objectivises it, which mind is only nature, very much as is the case of any dreamed creature, as the Buddha in the Diamond Sutra, and many others after him have so patiently explained to us.

This impersonal, universal mind or consciousness, is our true nature, our only nature, all, absolutely all, that we are, and is completely devoid of I-ness.

This is easy enough to understand, and it would be simple indeed if it were the ultimate truth, but it is not, for the obvious reason that no such thing as an objective ‘mind’ could exist, any more than an ‘I’ or any other object, as a thing-in-itself.

What it is, however, is totally devoid of any objective quality, and so cannot be visualized, conceptualized, or in any way referred to, for any such process would automatically render it an object of subject – which by definition it can never be.

This is because the mind in question is the unmanifested source of manifestation, the process of which is its division into subject and object; and antecedent to such division there can be no subject to perceive an object, and no object to be perceived by a subject.

Profoundly to understand this is Awakening to what is called ‘enlightenment’.

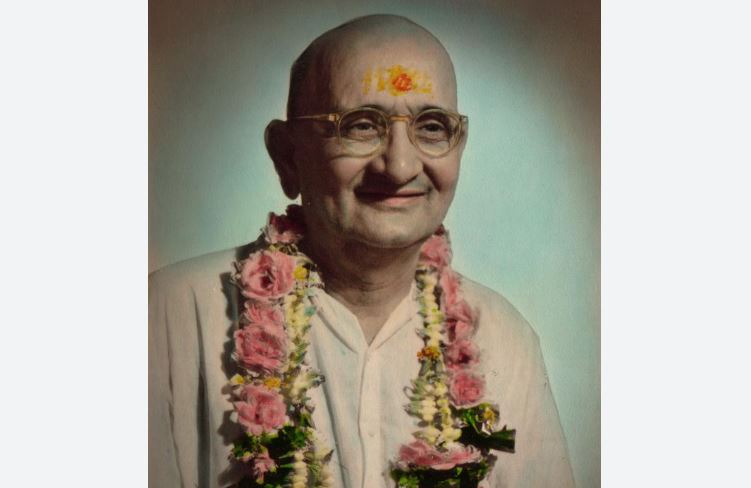

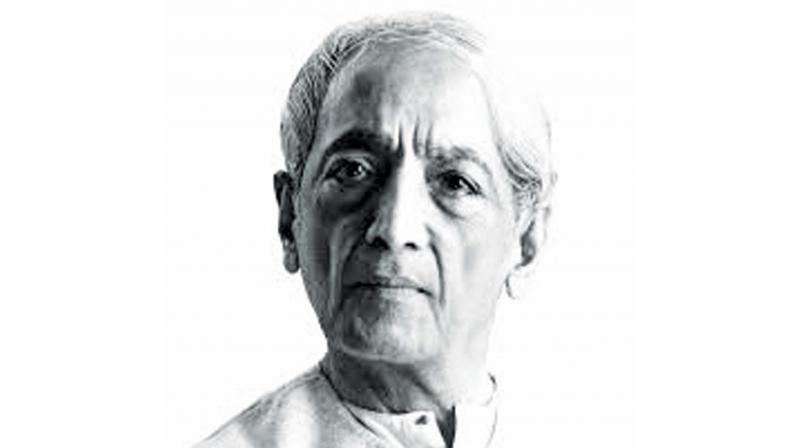

Excerpted from The Mountain Path, July 1964 . Wei Wu Wei, was a 20th-century Taoist philosopher and writer.

Wei Wu Wei (Terence James Stannus Gray)