The artist and poet William Blake said, “If the doors of perception were cleansed, every thing would appear to man as it is, Infinite. For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things through narrow chinks of his cavern.”

The artist and poet William Blake said, “If the doors of perception were cleansed, every thing would appear to man as it is, Infinite. For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things through narrow chinks of his cavern.”

What did he mean by this? How can a finite object, such as a tree, table, chair, person, or house be infinite?

Let us understand to begin with that the word ‘perception’ includes all five senses: seeing, hearing, touching, tasting and smelling.

Conventional thinking tells us that the experience of perception is divided into two essential ingredients: one, a subject that perceives and two, an object that is perceived. This understanding is enshrined in the structure of language with phrases such as, “I see the tree,” “I hear the wind,” “I touch the person,” “I taste the apple” and “I smell the flower.”

In each case, a subject – ‘I,’ the self – is joined to an object – the tree, wind, person, apple or flower – through an act of perceiving, that is, through an act of seeing, hearing, touching, tasting or smelling.

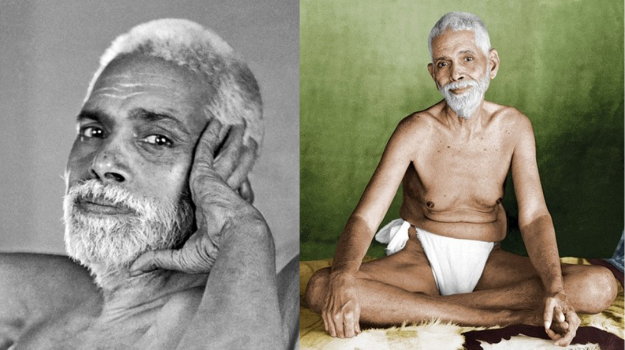

Now, in order to understand the nature of perception, we need to explore both sides of this equation – ‘I’, the subject, and the object or world. Traditionally, mystics have explored the nature of ‘I’, the self, and artists and scientists have explored the nature of the object or world.

In other words, mystics have tended to face inwards, directing their attention to the heart of their being or essential nature, and scientists and artists have tended to face outwards towards the objects of nature and the world.

At first glance it may seem that these two set out in opposite directions. However, if each party explores deeply enough, they inevitably come to the same conclusion. Indeed, it is only because in most cases, each party doesn’t explore deeply enough, that the conclusions of mystics on the one hand, and artists and scientists on the other, tend to differ so radically.

The painter Paul Cézanne said, “A time is coming when a single carrot, freshly observed, will trigger a revolution.” The revolution to which he referred is the coming together of these two perspectives – the convergence of the mystic’s, artist’s and scientist’s deepest understanding – and the implications this has for all aspects of our lives.

The Nature of the Self

Conventional thinking tells us that it is ‘I,’ the body/mind, that is aware of objects and the world. However, one simple, clear look at experience indicates that we are aware of the body and mind in just the same way that we are aware of objects and the world.

In other words, the body/mind is not the subject of experience. The body/mind is an object of experience, that appears and disappears like all other objects. Now what is the perceiving subject that we call ‘I,’ that knows or is aware of all these perceived objects, that is, that body, mind and world?

‘I’ refers to whatever it is that is aware of the objects of the body, mind and world. This ‘I’ cannot be found as any kind of object, that is, as a thought, feeling, sensation or perception. And yet ‘I’ am undeniably present and aware.

Hence, to be present and aware is inherent in ‘I,’ which for this reason is sometimes referred to as ‘Awareness,’ which simply means the presence of that which is aware. This Awareness that is our essential nature is like an aware, empty openness in which all experience takes place, but is not itself an experience.

Awareness is not located in time and is thus eternal or ever-present; it cannot be found in space and is thus infinite, that is, it has no finite or observable qualities.

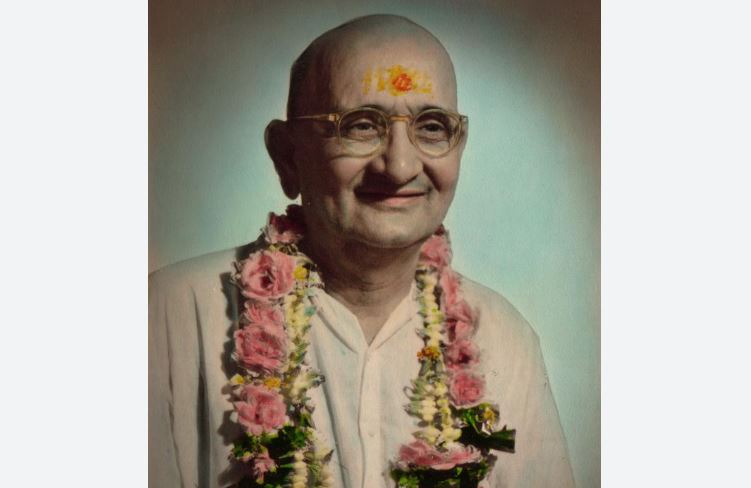

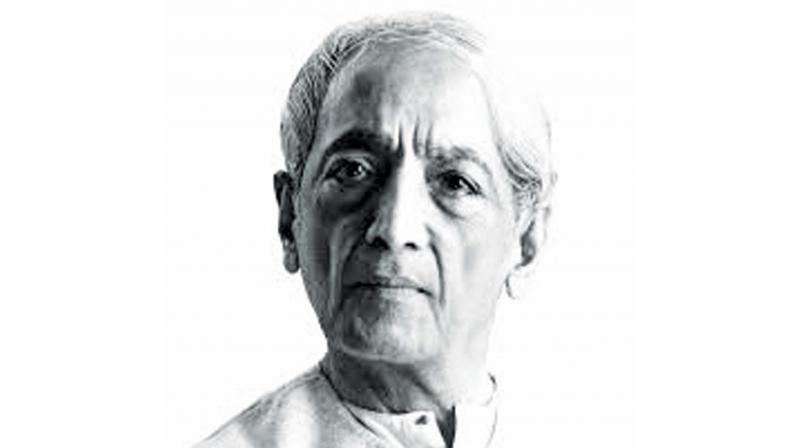

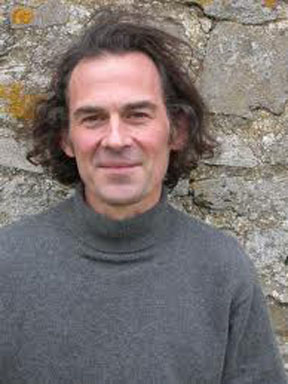

Rupert Spira, born in 1960, is a British potter and non-duality teacher

Rupert Spira