The mind, which is the medium of thinking, is more a process in the manner of a movement than just a thing operating in our body like an entity distinct from our physical embodiment. It is essentially a potential of energy capable of acting and reacting in respect of given circumstances, and maintaining an individuality of its own until the particular effect required to be produced by these actions and reactions is not produced.

The mind, which is the medium of thinking, is more a process in the manner of a movement than just a thing operating in our body like an entity distinct from our physical embodiment. It is essentially a potential of energy capable of acting and reacting in respect of given circumstances, and maintaining an individuality of its own until the particular effect required to be produced by these actions and reactions is not produced.

When the requisite effect is produced by this procedure of action and reaction, by an intricate pattern of movement of the nature of a process, the individuality of the mind overcomes itself. Often we say the mind dies. It does not actually die; it steps over the limitations of its erstwhile individuality and gathers up a momentum in the direction of another formation of itself, as long as it does not exhaust its potential for an immense kind of action and reaction in terms of the forms of sensation that we would call objects.

The objects, so-called, seen in this world are centers of evoking reactions from the mind in correspondence with the potential of the mind. That is to say, a particular mind does not act on every kind of object in the world, nor is it true that all the objects in all creation have a uniform type of impact on the mind.

The entire world does not present itself before any particular individual mind. A segment of creation, a part of this vast ocean of objects, alone is capable of entertaining a response from a particular mental mode. Likewise, no particular mind – your mind or my mind or anyone’s mind – can equally and uniformly react to all the things in the world. In other words, all things in the world cannot attract us, and also all things in the world cannot repel us.

It is not that we can have a desire for everything in the world at the same time, nor is it true that we can have an aversion for all things at the same time. There is a fractional partition, an individualized and highly self-centered activity going on in the form of the cognition of an object. A cognition is a mental perception of a thing. A sensory perception is generally distinguished from cognition, and is just called a percept.

The sensory perceptions also are activated by mental cognitions only. Our joys and sorrows are mental operations, not so much sensory activities. Our loves and hatreds do not originate from the eyes or the ears or any organ of sensation. These organs of sensations are harnessed for a particular purpose of activity by a mode of the mind, which is what we call love or hatred, like or dislike, action, etc. There is an internal operation going on which energizes the sense organs and drives this chariot of the body with the velocity of these horses of the senses in the direction of a set of objects to be acquired or avoided.

Actually, in any particular action of the mind – for instance, an activity in the direction of acquisition of some particular set of objects, loves of things – an automatic exclusion of other things also takes place. It is not that today we love a thing and tomorrow we hate another thing. The dual operation is a simultaneous effect produced. It cannot concentrate on any particular object for the purpose of acquiring it unless other objects are debarred entry into the mind at that particular moment.

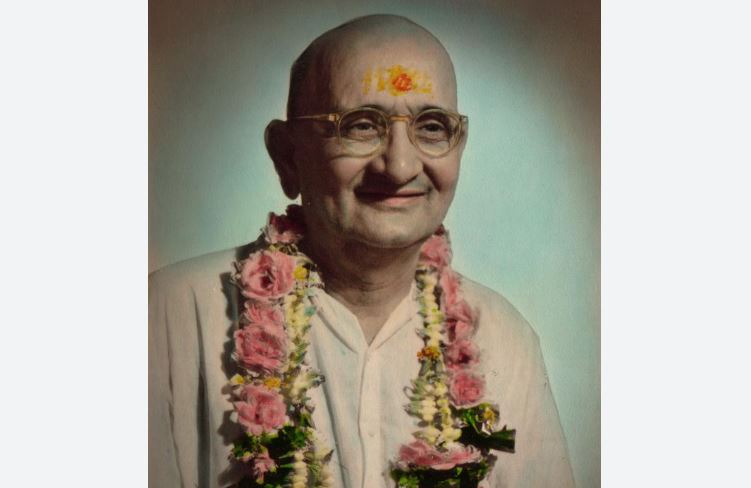

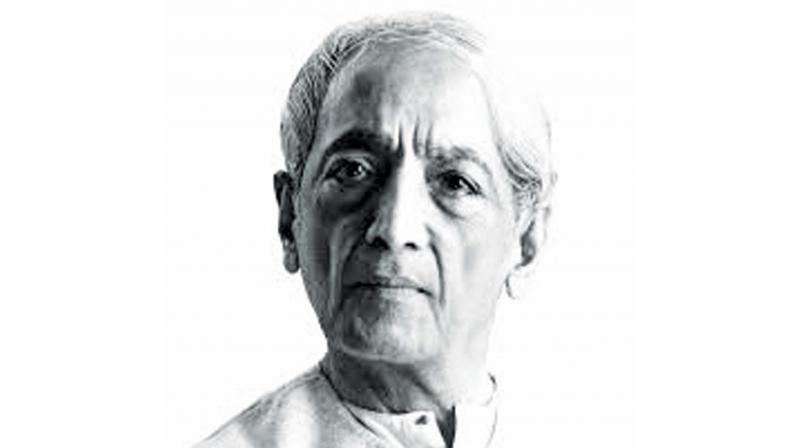

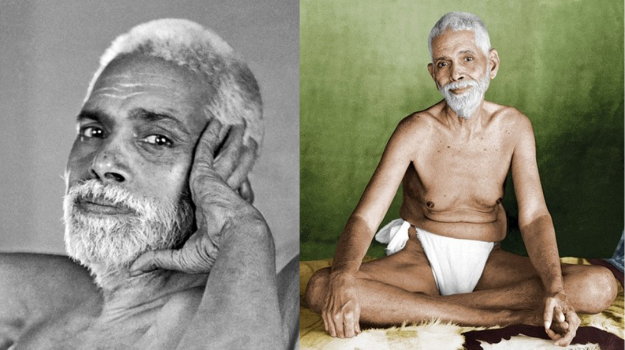

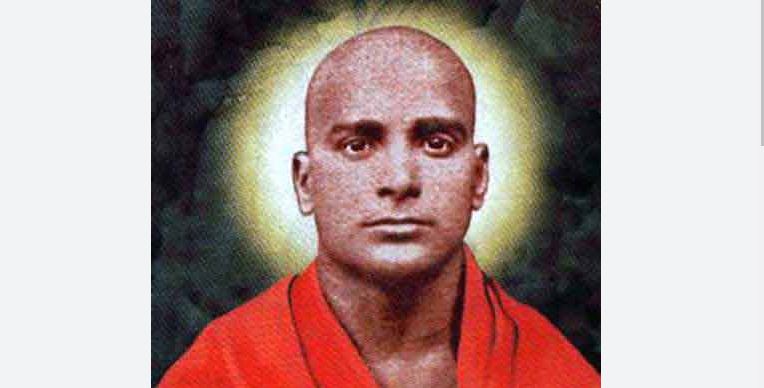

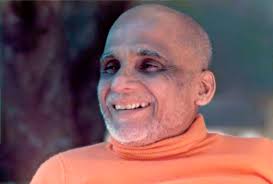

Swami Krishnananda

Excerpted from swami-krishnananda.org