The idea of the fourth dimension arose from the assumption that, in addition to the three dimensions known to our geometry, there exists a fourth, for some reason inaccessible and unknown to us, i.e. that in addition to the three perpendiculars known to us a mysterious fourth perpendicular is possible.

The idea of the fourth dimension arose from the assumption that, in addition to the three dimensions known to our geometry, there exists a fourth, for some reason inaccessible and unknown to us, i.e. that in addition to the three perpendiculars known to us a mysterious fourth perpendicular is possible.

In practice this assumption is based on the consideration that the world contains many things and phenomena about whose real existence there can be no doubt, but which are utterly beyond being measured in length, breadth and height and lie, as it were, outside three-dimensional space.

We may take as really existing that which produces a certain action, has certain functions, represents the cause of something else.

That which does not exist cannot produce any action, has no function, cannot be a cause.

But there are different kinds of existence. There is the physical existence, recognized by actions and functions of a certain kind; and there is the metaphysical existence, recognized by its actions and its functions.

A house exists, and the idea of good and evil exists. But they do not exist in the same way. One and the same method of proving existence cannot serve to prove the existence of a house and the existence of an idea. A house is a physical fact, an idea is a metaphysical fact. Both the physical and the metaphysical facts exist, but they exist differently.

In order to prove the idea of the division of good and evil – i.e. a metaphysical fact – I must prove its possibility. This will be sufficient. But if I prove that a house, i.e. a physical fact, can exist, it does not at all mean that it actually does exist. To prove that a man can own a house is no proof that he actually owns it.

Moreover, our relation to an idea and to a house is quite different.

By means of a certain effort a house can be destroyed – it can be burned or demolished. The house will cease to exist. But try to destroy an idea by effort. The more you fight against it, the more you argue, refute, ridicule it, the more the idea will grow, spread and gain strength.

On the other hand, silence, oblivion, non-doing, ‘non-resistance’ will annihilate, or at any rate weaken the idea. But silence, oblivion, will not harm a house or a stone. It is clear that the existence of a house and the existence of an idea are different existences.

We know a great many of such different existences. A book exists and the contents of a book exist. Notes exist, and the music they contain exists. A coin exists and the purchasing value of a coin exists. A word exists and the energy contained in it exists.

On the one hand we see a series of physical facts, on the other, a series of metaphysical facts. There are facts of the first kind and facts of the second kind; they both exist, but they exist differently.

From the ordinary positivist view it will appear very naive to speak of the purchasing value of a coin separately from the coin; of the energy of a word separately from the word; of the contents of a book separately from the book, and so on.

We all know that this is only ‘a manner of speech’, that actually the purchasing value, the energy of a word, the contents of a book, have no existence; they are only concepts by means of which we designate a series of phenomena in some way connected with them.

We see in things not only an outer aspect but an inner content. We know that this inner content constitutes an inalienable part of things, usually their main essence.

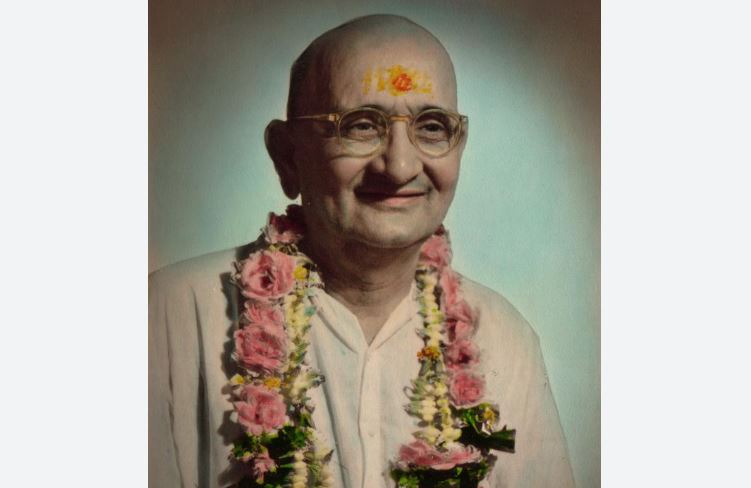

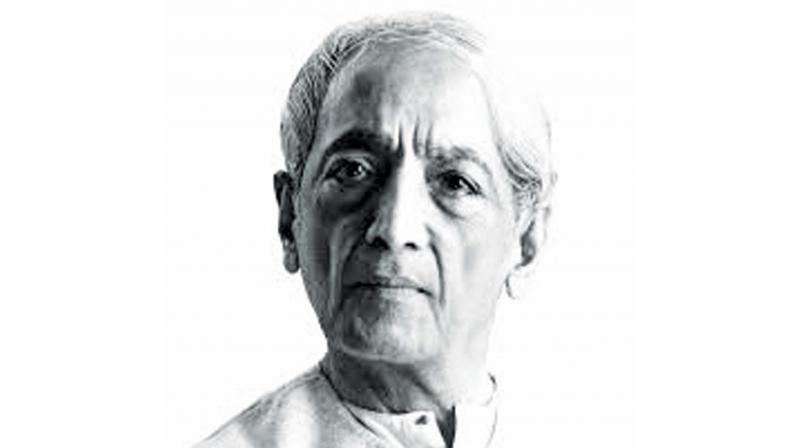

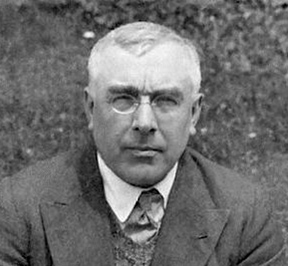

Excerpted from Tertium Organum (the third organ of thought). The 136th birth anniversary of Ouspensky was observed on March 4

P.D. Ouspensky