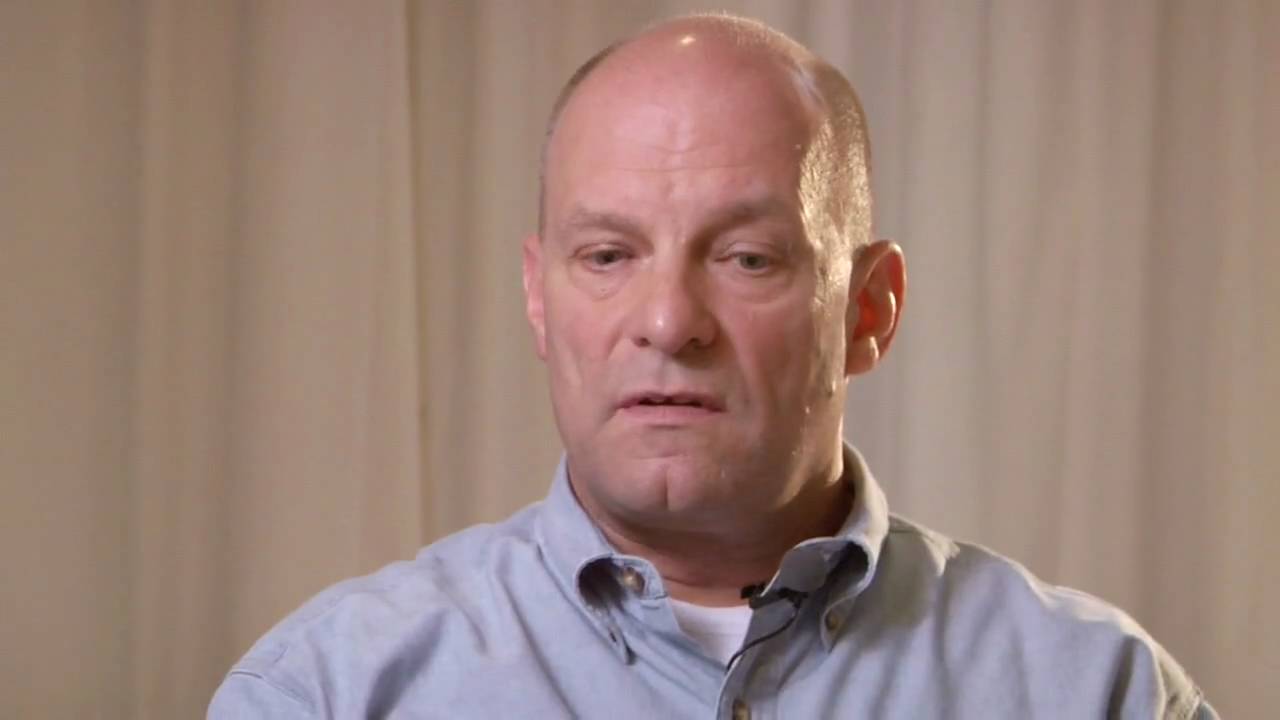

Greg Goode

The question of free will is from the perspective of the person. Does the person have free will? Many of the person’s actions are forced or determined by factors over which it has no control. Some of these actions are accompanied by the feeling of being lived, of being in the flow, in the “zone.” People often count these as the best times. But are at least some of the person’s decisions and actions freely chosen? To establish free will, it is not necessary to show that every action is free. Even one free action would be sufficient.

Take the following case: “Will that be coffee or tea?” “Hmmm, let me think…. I’ll have tea, thanks.”

From the perspective of the person, if the decision process is not analyzed, the actions and decisions seem to be perfect examples of free will. Upon analysis however, a free action and a free chooser cannot be found. A thought comes, followed by a desire, followed by a decision, followed by an action.

Tracing backwards, the action is controlled by the decision, the decision is controlled by the desire, the desire is prompted by the thought. The thought arises spontaneously, itself unbidden, un-asked-for, unchosen. First the thought is not there, then it is. Nowhere in this process can a free will be found. Nowhere can a freely-acting chooser be found.

It is even too much to say that the actions, decisions, desires and thoughts can control or prompt each other. These cause-and-effect dynamics are not even observed. Rather, they arise as inferences and conclusions about what happened, that is, they arise as thoughts that rise and fall.

In the above case, the decision might even be accompanied by a small feeling of freedom, lightness, and spaciousness. And maybe also accompanied by a thought, “I’m choosing tea but I could freely choose coffee instead.” But the feeling of freedom and the thought “I could” also arise unbidden. That is, the feeling of freedom is not freely chosen.

The person is not the locus of freedom.

The person and the rest of the world cannot be found apart from the awareness in which all things appear. The person, the mind, body and world arise as thoughts, feelings, and sensations. These are nothing other than objects in awareness, and are nothing other than awareness itself. The person does not experience; the person is experienced. As awareness, we are That to which these objects appear.

Thoughts, feelings, sensations – these objects arise from the background of silent awareness, they subsist in awareness, and they slip back into awareness. The awareness in which they appear is not itself an object but the background of all objects. It is our true nature. But the objects come and go unbidden, without autonomy. They are powerless and cannot do anything on their own. Objects cannot possess or contain freedom.

Is there freedom?

The silent awareness in which all objects appear is the true nature of all things. Awareness says YES to everything. Even if a NO arises, awareness says YES to the NO. Awareness is without resistance, without limits or edges, without refusal and without obstruction. Awareness is not free, it is freedom itself. What we truly are is not the person but this awareness, this freedom.

Excerpted from ‘The Enlightenment Secret.’ Greg Goode is a Doctor of Western philosophy as well as a self-realised teacher of Advaita and Buddhism and is equally at home with all approaches. He is a qualified Philosophical Counsellor in New York, where he also holds satsangs.