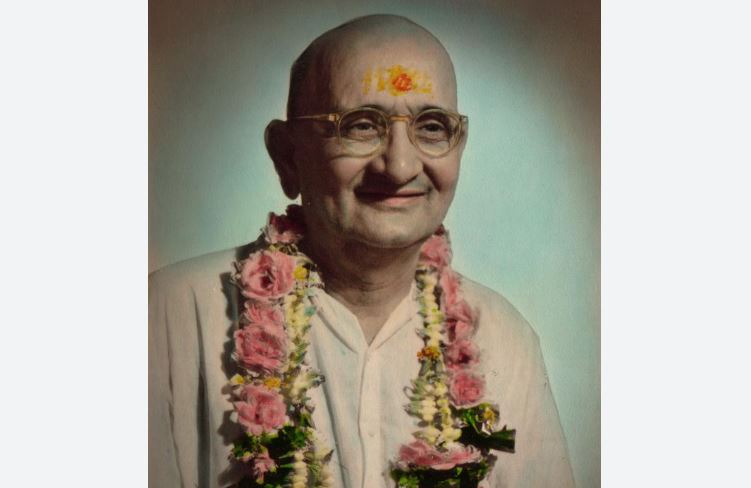

David R. Loy

What is truly distinctive about Buddhist Dharma? How does it differ from other religious traditions that also explain the world and our role within it? Foremost is the fact that no other spiritual path focuses so clearly on the intrinsic connection between dukkha and our delusive sense of self. They are not only related: for Buddhism the self is dukkha.

Although dukkha is usually translated as “suffering,” that is too narrow. The point of dukkha is that even those who are wealthy and healthy experience a basic dissatisfaction, a dis-ease, which continually festers. That we find life dissatisfactory, one damn problem after another, is not accidental—because it is the very nature of an unawakened sense-of-self to be bothered about something.

Pali Buddhism distinguishes three basic types of dukkha. Everything we usually identify as physical and mental suffering—including being separated from those we want to be with, and being stuck with those we don’t want to be with is included in the first type.

The second type is the dukkha due to impermanence. It’s the realization that, although I might be enjoying an ice-cream cone right now, it will soon be finished. The best example of this type is awareness of mortality, which haunts our appreciation of life. Knowing that death is inevitable casts a shadow that usually hinders our ability to live fully now.

The third type of dukkha is more difficult to understand because it’s connected with the delusion of self. It is dukkha due to sankhara, “conditioned states,” which is sometimes taken as a reference to the ripening of past karma. More generally, however, sankhara refers to the constructedness of all our experience, including the experience of self. When looked at from the other side, another term for this constructedness is anatta, “not-self.” There is no unconditioned self within our constructed sense of self, and this is the source of the deepest dukkha, our worst anguish.

This sense of being a self that is separate from the world I am in is illusory—in fact, it is our most dangerous delusion. Here we can benefit from what has become a truism in contemporary psychology, which has also realized that the sense of self is a psychological-social-linguistic construct: psychological, because the ego-self is a product of mental conditioning; social, because a sense of self develops in relation with other constructed selves; and linguistic, because acquiring a sense of self involves learning to use certain names and pronouns such as I, me, mine, myself, which create the illusion that there must be some thing being referred to. If the word cup refers to this thing I’m drinking coffee out of, then we mistakenly infer that I must refer to something in the same way. This is one of the ways language misleads us.

Excerpted from Money, Sex, War, Karma: Notes for a Buddhist Revolution. Ohio, US, based David Loy is an authorized lineage descendant and teacher of Zen