The grand old man of Indian writing was a friend of sorts to all people whose lives he came into. To me he was a little more. No, his hospitality never extended beyond a cola or plain water. He never shared his famous scotch with me even though on one occasion I’d bought a bottle of Black Label for him that was never delivered.

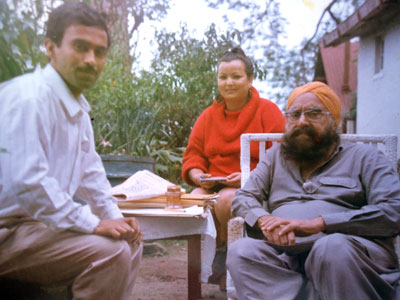

It was some 20 years back, in 1994, when I first met Khushwant Singh for my first cover story – a profile of the writer in Gentleman. His book, ‘Not a Nice man to Know’ was just out then. When I went to give him a copy of the magazine he was delighted.

‘A Nice Man to Know’, the title of my story had charmed him. And thus opened his door to me – the door on which was written the famous line, ‘Do not ring the bell if you’re not expected!’ Many a diplomat and neta had to turn back from that door for having arrived without an appointment.

To me that door was opened often with a radiant smile. Very often he was sitting on his sofa, his legs outstretched on the cane moora by the fireplace. His wife was always present in the room whenever we had met, and then she was gone. I continued to visit him, and he appeared lonely.

Once, I took along a curious friend to meet him. The friend was disappointed by the simplicity of his home. Those days there was a firing incident in a famous God man’s compound in Bangalore – or was it Hyderabad? – that was making headlines. Khushwant, curious as ever asked me if I had some inside news. Then to mine, and my friend’s shock and horror he said, “That man (god man) is a gandu…” The rest of it, told in Hindi, is unprintable. Translated, it would read, “He buggers and gets buggered as well.”

That was unadulterated Khushwant Singh. He never cloaked his words in the veneer of decency. But to even suggest that he was not a decent man would be unthinkable. The image of a debauched man frolicking with wine and women was a picture he had deliberately created to his legion of fans running into millions.

Yes, it is true he reveled in the company of women and he loved his evening tipple. Many were fooled into believing he was a debauched man. Even I had to pay a heavy price for this. I was with UNHCR then. Khushwant readily agreed to do a shoot for a film on refugees that I was making, where he spoke as a former refugee from Pakistan. Later, I had taken my boss Irene Khan, to meet him at his home. They were an instant hit. I later convinced Khushwant to do a poster for UNHCR to which, he again readily agreed.

By the time the poster was to be made Irene had left for UNHCR headquarters in Geneva and I had a new African boss. He hauled me up one fine afternoon for giving unsound advice on the poster. “Ashim your advice for featuring Khushwant Singh on a UN Refugee poster was not good,” he had said.

I was dumbfounded, but defended myself rather poorly. Later, when I asked him how he had come to such a conclusion, he produced a lady colleague. She and a few of her cronies were giggling, “Oh everyone knows about his drinking and womanizing.”

I was too disgusted for words. How I wished they were a little better read and told them so. The poster project with Khushwant was dropped. I was embarrassed. Khushwant had spent an entire afternoon doing a photo-shoot wearing a UNHCR tee shirt! My visits to him became fewer.

A few years later, out of UNHCR, I was interviewing him again for a news channel. He had just been given the ‘Honest Man of the Year’ award instituted by Sulabh International’s Bindeshwar Pathak. The citation also carried a cash prize of a million rupees. It wasn’t a small amount then.

Among many other questions I asked him what he intended doing with the money. I was expecting an exalted well thought out response, maybe of donating it to some noble cause, when pat came Khushwant’s response with a loud guffaw. “I’m going to spoil myself with that money!”

Who else could give such a disarmingly candid answer like that? Khushwant Singh, above all else, was an honest man. Not surprisingly, he tore many a reputation to shreds in what used to be a delightfully malicious column. The author of over thirty books, some of them classics like ‘Train to Pakistan’, ‘I shall not hear the Nightingale’ and ‘Delhi’ did not take his own reputation very seriously. He also had the uncommon ability to laugh at himself and his community; the result, a clutch of joke books mostly on sardars. But though an agnostic he personally considered ‘The History of Sikhs’ – a scholarly work – one his best books.

Was he a helpful person? In my case, he twice recommended me to people when I was out of a job. When both attempts failed, he laughed wistfully saying that he no longer had clout. When he was a Director at Penguin he also reviewed my manuscript and gave me some useful tips, one of them, asking me to cut down on descriptions.

Alas, when ‘The Sergeant’s Son’ was out in January 2013 I could not personally hand him a copy of my debut novel. By then he was quite ill and the caretaker who took the phone said he did not meet people any more. I still took a chance one evening and the caretaker was kind enough to allow me in. Just as I was to be in his presence a young lady imperiously blocked my way. “He does not see anyone,” his granddaughter said haughtily.

Like a nervous school boy I held my book and said, I wanted to personally present him a copy. “Tell him my name, Ashim Choudhury.” She relented a bit. Looking in his direction near the fireplace, hidden from my view, she asked loudly, “Are you expecting anybody.” She repeated the question. Apparently, he nodded negatively.

“Sorry,” said the young lady, “I cannot allow you in.”

It was one of my saddest days. I was so close to my guruji and yet so far. And now, he is gone forever.

(Author of The Sergeant’s Son;blog:www.as-himch13.blogspot.in)

Ashim Choudhury