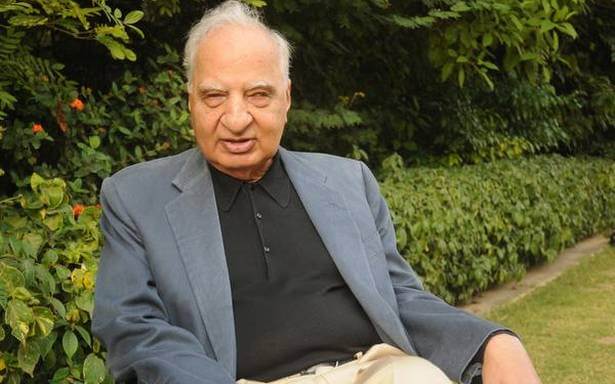

NEW YORK: Celebrated Indian-American novelist Ved Mehta, who overcame blindness and became widely known as the 20th-century writer most responsible for introducing American readers to India, has died at his home here at the age of 86.

The New Yorker magazine, where he had been a staff writer for 33 years, reported that Mehta died on Saturday 9 January.

“Mehta, a writer for The New Yorker for more than thirty years, died at the age of eighty-six, on Saturday morning,’ it said.

Born in pre-partition Lahore to a well-off Punjabi family in 1934, Mehta lost his eyesight when he was three years old to meningitis. He, however, did not let his impairment get in the way of a flourishing career or stop him from showcasing his literary prowess to the world.

He was determined to apprehend the world around him with maximal accuracy and to describe it as best he could.

“I felt that blindness was a terrible impediment, and that if only I exerted myself, and did everything my big sisters and big brother did, I could somehow become exactly like them,” he wrote.

Best known for his 12-volume memoir, which focused on the troubled modern history of India and his early struggles with blindness, Mehta’s 24 books included volumes of reportage on India, among them “Walking the Indian Streets” (1960), “Portrait of India” (1970) and “Mahatma Gandhi and His Apostles” (1977), as well as explorations of philosophy, theology and linguistics.

“Daddyji” was the first installment in what was to become a 12-volume series of autobiographical works, known collectively as Continents of Exile.

“Ved Mehta has established himself as one of the magazine’s most imposing figures, The New Yorker’s storied editor William Shawn, who hired him as a staff writer in 1961, told The New York Times in 1982.

“He writes about serious matters without solemnity, about scholarly matters without pedantry, about abstruse matters without obscurity, Shawn had said.

The recipient of a MacArthur Foundation genius grant in 1982, Mehta was long praised by critics for his forthright, luminous prose with its informal elegance, diamond clarity and hypnotic power, as The Sunday Herald of Glasgow put it in a 2005 profile, the New York Times reported.

Mehta composed all of his work orally, dictating long swaths to an assistant, who read them back again and again for him to polish until the work shone like a mirror. He could rework a single article more than a hundred times, he often said, the report said.

One of the most striking hallmarks of Mehta’s prose was its profusion of visual description: of the rich and varied landscapes he encountered, of the people he interviewed, of the cities he visited, the NYT report said.

Mehta walked the streets of the city without a cane or a seeing-eye dog, and he bristled when someone dared try to assist him.

Mehta came to the United States when he was 15 years old, and attended the Arkansas School for the Blind, in Little Rock. After studying at Pomona College and Oxford University, he began to flourish in his working life as a writer.

He joined the magazine when he was 26 and, for more than three decades, wrote a stream of pieces, many of them appearing in multipart series. He wrote about Oxford dons, theology, Indian politics, and many other subjects.

Madhur Jaffrey, the Indian-born actress and cookbook author, once told Maureen Dowd, of the New York Times, that when she first met Mehta, I tried to take his arm to help. He gave me a shove, and we’ve been friends ever since, the New Yorker reported.

Some of his most fascinating work includes A Battle Against the Bewitchment of Our Intelligence (1961), a portrait of British intellectual life and the philosophical debates of the time; John Is Easy to Please (1971), a piece about the young linguist Noam Chomsky and the critics of his theory of transformational grammar; and, in 1976, a three-part Profile of Mahatma Gandhi, the report said. PTI