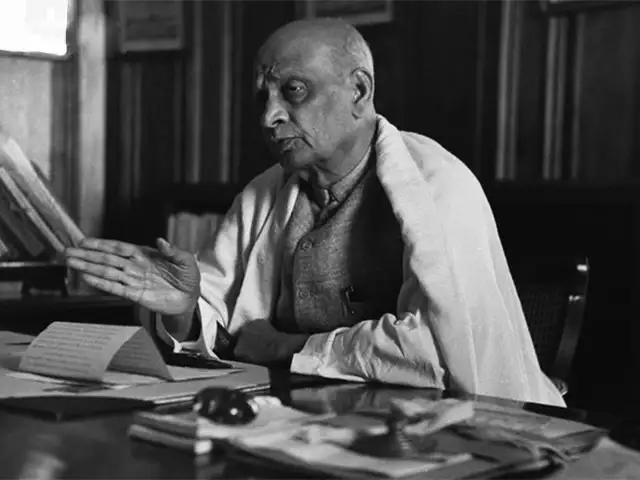

NEW DELHI: Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel was the master of epistemology. Equally, like Nehru, he had complete disregard for the popinjay princelings with their quaint idiosyncrasies and monumental egos.

On December 16, 1947, Sardar explained the background and the policy underlying the controversial merger of the Eastern States. It had created consternation amongst the pack of princes impacted and those who were to be impacted subsequently.

To allay their fears, Sardar laid down a template of sorts explaining the nuances behind the act and why it was required to bind the new India into one whole, preparing the way for the Republic in the future. Think of the complexities that Sardar and his assistant, V.P. Menon, who doesn’t get enough credit for his service to India, had to engage with.

Princes large and small with their own baggage trying to be convinced to integrate with other principalities and then further into the Union of India. Princes used to freedom, indulging in feudal acts of tyranny and keeping their subjects in perpetual serfdom.

The statement laid stress on the fact that democracy and democratic institutions could function efficiently only where the unit to which these were applied could subsist in a fairly autonomous existence. Integration was clearly and unmistakably indicated where, on account of its smallness of size; its isolation; its inseparable link with a neighbouring autonomous territory in practically all matters of everyday life; its inadequacy of resources to open up its economic potential; the backwardness of its people; and its sheer incapacity to shoulder a self-contained administration, a state was unable to afford a modern system of government.

It went on to say that in many of the Eastern States, large-scale unrest had already gripped the people; while in others, the rumblings of the storm were clearly to be heard. In such circumstances and after careful and anxious thought, Sardar had come to the conclusion that for smaller states there was no alternative to integration. He paid a tribute to the rulers, who had shown commendable appreciation of the realities of the situation, and a benevolent regard for the public good.

The princes had by their act of abnegation purchased in perpetuity their right to claim the devotion of their people. The statement concluded by drawing attention to the states involved some 56,000 square miles of territory with a population of about 8 million, a gross revenue of about Rs 2 crore and an immense potential for the future.

It was but natural that this merger should provoke criticism from princely circles. The question was raised by them when they had a conference with Lord Mountbatten on January 7, 1948. The conference was attended by the rulers and dewans of Jodhpur, Bikaner, Bhopal, Rewa, Kota and Alwar, as well as the dewans of Kashmir, Indore, Kolhapur, Udaipur and Bhopal, and representatives of Travancore, Cochin, Patiala and Jodhpur.

In his inimitable way, Lord Mountbatten defended the merger of the Orissa and Chattisgarh States. He explained the system of mediatisation, or merger, introduced by Napoleon in 1806 and added that his own family came from the Grand Duchy of Hesse, which had absorbed about a dozen small principalities. The ruling families of the states thus merged were able to avoid the impact of the German Revolution of 1918. He was personally very much in favour of the system of mediatisation.

Lord Mountbatten emphasised that there was no intention of applying the merger system to the larger states. Indeed, the rulers of the larger states should welcome the principle of merger being applied to the smaller ones because the entire Indian States system would stand condemned by the example of its worst participants.

Menon recounts that the Maharajah of Mayurbhanj had kept aloof from the merger on the ground that he had granted responsible government and so could not move without consulting his ministers.

In the course of a year, the maharaja said, the so-called popular ministers had run through the major part of the savings of the state, the administration was almost at a standstill and there was considerable unrest among the people.

“The Maharaja came to me and confessed that it was a mistake on his part not to have merged his State along with the other Orissa States,” Menon recalled. “He told me frankly that if something was not done immediately, the State would go bankrupt. He was loath to see the savings of the State, which he had built up with great difficulty, recklessly squandered away. He pleaded that the State should be taken over by the Government of India at once. I discussed the matter with the Premier of Mayurbhanj, who agreed.”

Menon added: “On October 17, 1948, the Maharaja signed an Instrument of Merger. The State was taken over by the Government of India on November 9 and a Chief Commissioner was appointed to administer it. Later, however, we decided that Mayurbhanj should go to Orissa, as it was linguistically and culturally linked with that province.”

An apocryphal story told about the Mayurbhanj affair is that the secretary of the Maharaja arrived at Pandit Nehru’s residence to meet his private secretary D.N. Kachru. He asked Kachru if he could be nominated to the newly formed IAS as a reward for persuading the Maharaja to sign the Instrument of Accession. Kachru knew that Nehru wouldn’t agree to such a suggestion. So, Kachru asked him to talk directly to V.P. Menon.

When his case was put up for Sardar’s approval, the States Minister responded typically: “What is a post for a State? How does it matter? Get me Mayurbhanj.” Within a few days, the Maharaja had acceded to the Union of India after dithering for long. The Secretary incidentally was nominated to the then Central Provinces (now Madhya Pradesh) IAS cadre subsequently.

It is said that Patel balanced Nehru’s grand sweep, vision and idealism with hard-nosed realpolitik and pragmatism, and together, despite differences, they formed a cohesive winning team. Gandhiji needed both, they were his fraternal twin political heirs, and they needed each other to actualise the dream for freedom and independence.

Immediately thereafter, in rapid succession, the great swoop down began with V.P. Menon, sometimes accompanied by Sardar Patel, criss-crossing the length and breadth of India, cutting deals, breaking logjams, cajoling and sometimes threatening princes and unions to accede to India. This was done smoothly, there were setbacks, but eventually more or less everyone came on board.

Kathiawar was next and the Saurashtra Union was complicated. Kathiawar comprised the 14-salute states of Junagadh, Nawanagar, Bhavnagar, Dhrangadhra, Porbandar, Morvi, Gondal, Jafrabad, Wankaner, Palitana, Dhrol, Limbdi, Rajkot and Wadhwan; 17 non-salute states; and 191 other small states exercising varying degrees of jurisdiction. The area was a little over 22,000 square miles with a population of nearly 4 million.

The following extract from an article which appeared in ‘The Tribune’ in July 1939 gives a graphic picture of the problem of the smaller states in Kathiawar:

“As many as 46 states in this Agency have an area of two or less than two square miles each. Eight of them, namely, Bodanoness, Gandhol, Morchopra, Panchabda, Samadhiala, Chabbadia, Sanala, Satanoness and Vangadhra are just over half a mile each in area. Yet none of these is the smallest state in Kathiawar! That distinction goes to Vejanoness, which has an area of 0.29 square mile, a population of 206 souls, and an income of Rs 500 a year.

There is nothing in the annals of the Indian states — Gujarat States excepted — which can beat this record. This is not all. Even these tiny principalities do not seem to be indivisible units. Some of them are claimed by more than one sovereign, officially described as a shareholder.

“Thus Dahida, with an area of two square miles, has six shareholders, and Godhula and Khijadia Dosaji, being one square mile each in extent, have two shareholders each; while Sanala, 0.51 square mile in area, is put against two shareholders. Such instances can be easily multiplied up to 30 to 40.”

There was procrastination and fear among several of these rulers. Finally, on January 21, 1948, to allay their fears and lurking suspicions, and safeguard their interests, a draft Covenant was created which was to be signed only by the rulers of salute and non-salute states.

(Sandeep Bamzai is the Editor-In-Chief of IANS and author of ‘Princestan: How Nehru, Patel and Mountbatten Made India‘ (Rupa), which won the Kalinga Literary Festival (KLF) Book Award 2020-21 in the non-fiction category.)