My wife and I once went into a café in San Francisco during the lunch hour, and the people working there were in such a flurry that one nearly hit the head of the fellow next to me with a plate.

She hadn’t lost her temper, she had no grievance against him, but the sheer speed of her movement so unnerved her that the plate flew out of her hands.

A great deal of carelessness results from hurry, and all kinds of accidents that we choose to call chance or fate or luck are actually simple processes of cause and effect. We do not see the causal connections because we move too fast to notice.

Speeded-up people can be likened to automata, to robots. Perhaps you remember that insightful Chaplin movie Modern Times? Charlie stands at an assembly line in a factory, and for eight hours a day he tightens a nut with his wrench as each piece goes by. From time to time the boss turns up the pace of the conveyor belt, and poor Charlie has to work even faster.

Throughout the day he makes the same movement with his arm. When he comes out after eight hours, he cannot stop. Though he has no wrench, he makes the same gesture all the way home, to the amazement of the passersby.

This is what happens to speeded-up people. They become automatic, which means they have no freedom and no choices, only compulsions. Since they take no time to reflect on things, they gradually lose the capacity for reflection.

Without reflection, how can we change? We first have to be able to sit back, examine ourselves with detachment, and search out our patterns of behavior.

When we go faster and faster, we grow more and more insensitive to the needs of everyone around. We become dull, blunted, imperceptive. In the morning, for instance, when we are moving like a launched missile, our vigilance falls; we may hurt the feelings of our children or partner and never know it at all.

We need to remember, too, that hurry is contagious. When a person comes rushing into a room with an agitated mind, it has an impact on the people there. If they are not very secure themselves, they will become even more agitated by the sight of someone hurrying about out of control.

Suppose the family is trying to get breakfast when in races the high school junior already late for school. She calls out to remind her mother to pick up her shoes from the repair shop on the way to the supermarket.

She scrambles about trying to remember where she left her notebook. She spills some milk pouring it on her cereal, which she tries to eat standing up.

In a few minutes the relaxed atmosphere in the room has dissipated, and everyone becomes edgy.

Happily, the opposite also holds true. When someone at peace and free from hurry enters a room, that person has a calming effect on everyone present. Such collectedness too is contagious. Until we learn to act in freedom, most of us will be temporarily calmed or agitated by those we are around.

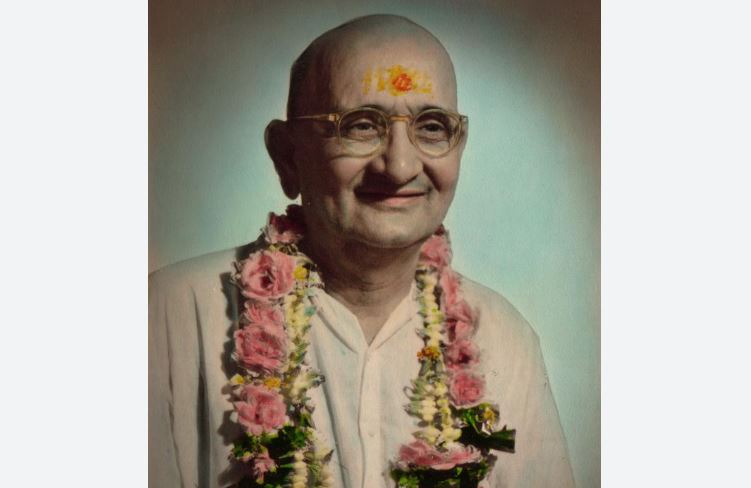

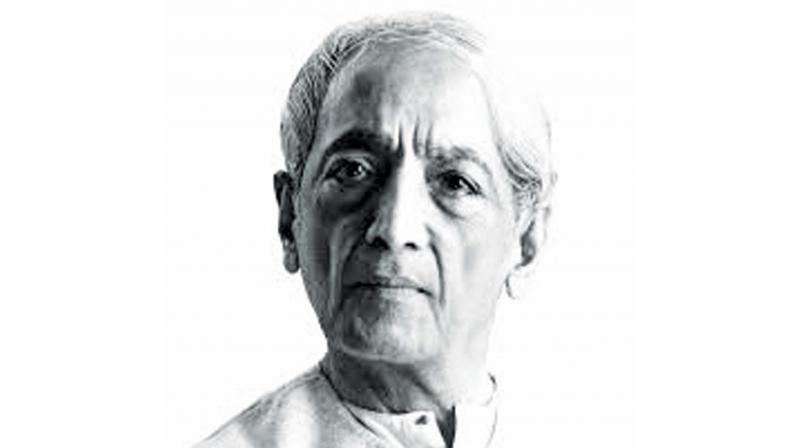

The 102nd birth anniversary of Eknath Easwaran will be observed on December 17

Eknath Easwaran