Unique astronomy without telescope

Unique astronomy without telescope

India Post News Service

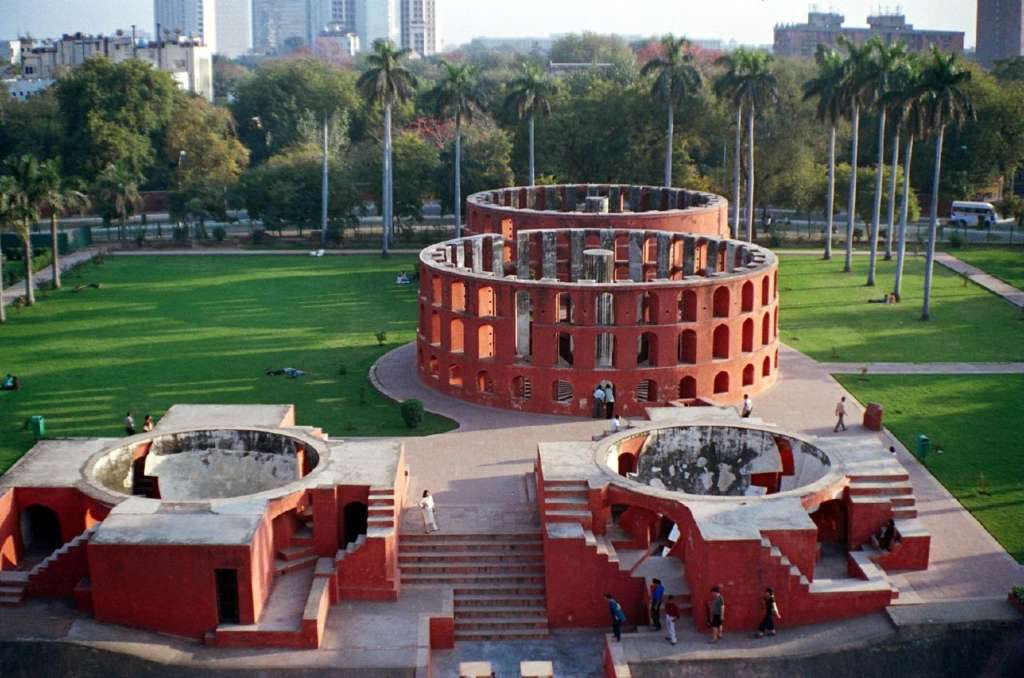

Between 1724 and 1730 Maharajah Sawaii Jai Singh II of Jaipur constructed five astronomical observatories in north India. The observatories, or “Jantar Mantars” as they are commonly known, incorporate multiple buildings of unique form, each with a specialized function for astronomical measurement. These structures with their striking combinations of geometric forms at large scale have captivated the attention of architects, artists, and art historians worldwide, yet remain largely unknown to the general public.

The decision to build multiple observatories at large distances from one another was in part a quest for accuracy; the ability to compare readings from different coordinates. But the observatories may also have played a role in strengthening Jai Singh’s political position in regions where he had gained authority. It is also noteworthy that the sites Jai Singh chose have historical, political, or religious significance:

Delhi was an ancient city and the seat of the Mughal Empire.

Jaipur was founded by Jai Singh in 1726 to become the new capitol of his kingdom.

Ujjain was the former capital of the Malwa province and is located on the prime meridian established by the ancient Hindu canons of astronomy.

Varanasi was an ancient center of learning, and reputedly the oldest continuously inhabited city in the world.

Mathura was the legendary city of Krishna.

Passionately interested in mathematics and astronomy, Jai Singh adapted and added to the designs of earlier sight-based observatories to create a unique architecture for astronomical measurement. Jai Singh was influenced primarily by the Islamic school of astronomy, and had studied the work of the great astronomers of this tradition.

Early Greek and Persian observatories contained elements that Jai Singh incorporated into his designs, but the instruments of the Jantar Mantar, as Jai Singh’s observatories have come to be known, are more complex and at much greater scale than any that had come before.

One of the remarkable aspects of Jai Singh’s observatories is that each site is distinctly different in size, layout, and style. While the instruments he designed are essentially the same in principle, the versions at different sites vary in size, materials, and construction.

The first observatory to be built was the observatory at Delhi in 1724. The Jaipur observatory, the most elaborate, was begun by 1728. Smaller observatories were built in Benares, Ujjain, and Mathura. Of the five observatories, all except the observatory at Mathura still exist and are publicly accessible. The Mathura observatory, and the fort in which it was housed, were demolished just before 1857.

The observatories at Delhi and Jaipur are the best known and most visited, since they are within major tourist destinations. They also feature the largest versions of the instruments Jai Singh built, and the Jaipur observatory houses the greatest number and variety of instruments.

On the topic of why Jai Singh chose not to use telescopes in his observatories, Anisha Shekhar Mukherji in her book ‘Jantar Mantar: Maharajah Sawaii Jai Singh’s Observatory in Delhi,’ says Sawaii Jai Singh was aiming for a clearer picture of the entire sky and the systems that governed it, for which his following seven Yantras were eminently suitable:

Samrat Yantra; Rama Yantra; Jai Prakash; Digamsa Yantra; Nadivalaya Yantra; Daksinottara Bhitti; Unnatamsha Yantra. (Details of the Yantras available on jantarmantar.org)

When Jai Singh designed the observatories, one of his foremost objectives was to create astronomical instruments that would be more accurate and permanent than the brass instruments in use at the time. His solution was to make them large, really large, and to make them of stone and masonry. This simple yet remarkable decision brought forth a collection of large scale structures for the measurement of celestial movement that is unequalled today.

Among the many startling impressions for a visitor to one of the observatories, is the scale of the instruments. One is literally enveloped, and confronted with a space that is both aesthetic and mathematical. The time scale of the Samrat Yantra at Jaipur, for example, includes subdivisions as fine as two seconds, and as one watches, the motion of the gnomon’s shadow becomes a palpable experience of earth’s cosmic motion.

Just at the Jaipur site alone are nineteen futurist architectural instruments that are now counted as a UNESCO World Heritage site. The 73-foot-tall sundial has held the world record for over three centuries as the world’s largest sundial.

Among his many later accomplishments, Jai Singh founded the city of Jaipur which bears his name, and was responsible for much of its design.

Courtesy jantarmantar.org