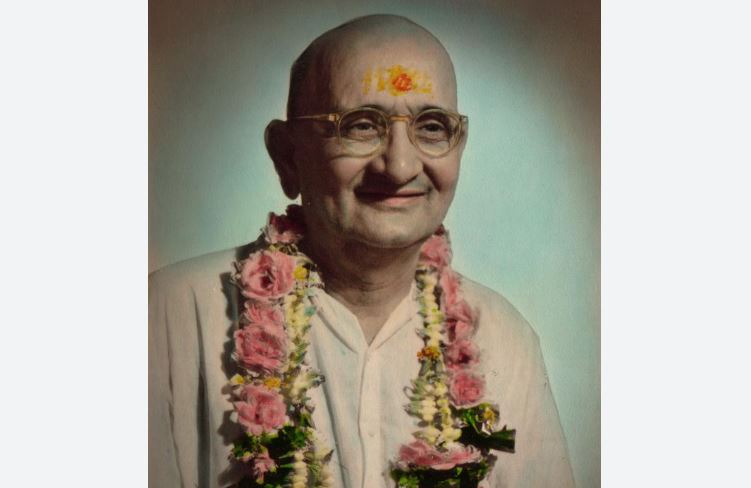

Pema Chödrön

If there is one skill that is not stressed very much, but is really needed, it is knowing how to fail. There is a Samuel Beckett quote that goes “Try again. Fail again. Fail better.” That quote is what will help you more than anything else in the next year, the next ten years, the next twenty years, for as long as you live, until you drop dead.

There is a lot of emphasis on succeeding. We all want to succeed, especially if we consider success to be things working out the way we want them to. Failing is what we don’t usually get a lot of preparation for.

So how to fail?

We usually think of failure as something that happens to us from the outside: We can’t get in a good relationship or we are in a relationship that ends painfully; we can’t get a job or we are fired from the job we have; or any number of ways in which things are not how we want them to be.

There are usually two ways that we deal with that. The first is that we blame it on some other—our boss, our partner, whoever. The second is that we feel really bad about ourselves and label ourselves a failure.

This is what we need a lot of help with: this feeling that there is something fundamentally wrong with us, that we are the failure because of the relationship or the job or whatever it is that didn’t work out—botched opportunities, doing something that flops, heartbreak of all kinds.

One of the ways to help yourself is to begin to question what is really happening when there is a failure.

It can be hard to tell what’s a failure and what’s just something that is shifting your life in a different direction. In other words, failure can be the portal to creativity, to learning something new, to having a fresh perspective.

Getting curious about outer circumstances and how they are impacting you, noticing what words come out and what your internal discussion is—this is the key.

Out of that space of failure can come addictions of all kinds—addictions because we do not want to feel it, because we want to escape, because we want to numb ourselves. Out of that space can come aggression, striking out, violence. Out of that space can come a lot of ugly things.

It is out of this same space that come our best human qualities of bravery, kindness, and the ability to really reach out to and care about each other. It’s where real communication with other people starts to happen, because it’s a very unguarded, wide-open space in which you can go beyond the blame and just feel the bleedingness of it, the raw-meat quality of it.

Pema Chödrön is an American Tibetan Buddhist. Adapted from her address to the 2014 graduating class of Naropa University in Boulder, Colorado.