SAN FRANCISCO: It turns out the man behind Mickey Mouse liked quirky cats.

Besides his love of wholesome entertainment, Walt Disney also had an appreciation for the eccentric that led to a short-lived partnership and decades-long friendship with surrealistic artist Salvador Dali.

Although their styles and personalities were dramatically different, Disney and Dali shared a fascination with the fantastic. They brought their vivid imaginations together shortly after World War II to work on an animated feature called “Destino,” which wasn’t completed until long after their deaths.

Even after they abandoned “Destino,” the two artists remained in touch and even traveled to each other’s homes, swapping fishing stories and periodically discussing plans to make a movie based on “Don Quixote.” That dream was never realized. Disney died in 1966. Dali, who was three years younger, died in 1989.

The improbable bond between the mastermind of Disneyland and the Spanish painter of reality-bending images will be explored in an exhibit running from July 10 through Jan. 3 at the Walt Disney Family Museum in San Francisco. It will then shift to the Dali Museum in St. Petersburg, Florida.

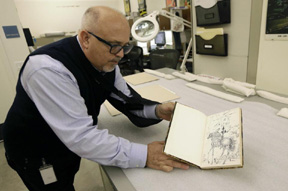

The exhibit will feature “Destino” storyboards, letters exchanged between the two men, photographs, voice recordings and rarely seen artwork, including a drawing of Don Quixote that Dali did for Disney in 1957 inside a book, Shakespeare’s “Macbeth.”

“This will show an angle of Walt that people don’t normally think of – he wasn’t just all about family-friendly stuff,” says filmmaker Ted Nicolaou, the exhibit’s curator. “He wasn’t dark, but he dealt in dreams and fantastical images. He was a man ready to experiment in any way possible.”

Dali, a pioneer in Europe’s surrealistic movement, thought Disney might be a kindred spirit when he saw some of Disney’s early animation in the “Silly Symphony” series that ran from 1929 through 1939.

Nicolaou said a “Silly Symphony” skit featuring dancing skeletons particularly appealed to Dali, whose paintings of melting clocks, apparitions, monsters and other creatures often border on the hallucinogenic.

When he first came to California in 1937, Dali sought out another artist whom he considered to be a master in surrealism – the comedian Harpo Marx. He also saw surrealistic undertones in the work of Disney and filmmaker Cecil B. DeMille.

Disney had become intrigued with Dali, too. After reading the artist’s autobiography, he sent his copy to Dali in 1944 seeking an autograph. He also suggested that Dali work on a piece of animation to be packaged into a film along the lines of Disney’s 1940 musical, “Fantasia.”

The partnership didn’t come to fruition until late 1945, shortly after Disney and Dali met for the first time at a Hollywood dinner party hosted by movie studio mogul Jack Warner. By that time, Dali had already completed some work on a dream sequence in an Alfred Hitchcock movie, “Spellbound.”

Given the wide range of choices in Disney’s vast music library, Dali decided to set his animation to a Spanish ballad called “Destino” because the title resonated with his interest in destiny. Disney assigned one of his most trusted animators, John Hench, to assist Dali on “Destino.”

While working with Hench to produce more than 200 storyboards and sketches for “Destino,” Dali struggled to come up with a plot that made sense to Disney. The two men’s differences began to crystallize in a 1946 interview when they were asked about their visions for “Destino.” Dali described it as “a magical exposition of life in the labyrinth of time” while Disney saw it as “a simple love story – boy meets girl.”

Their differences widened when Dali began to insert sketches of baseball players into “Destino.” Exasperated that about $70,000 had already been spent on a project that didn’t seem to be progressing, Disney decided to scrap it.

“It got a little too wild for Walt, so he quietly pulled the plug,” Nicolaou says. “I think Dali was embarrassed and hurt by it.”

The professional split apparently didn’t damage Dali’s friendship with Disney. During the 1950s, Dali visited Disney’s home, where he rode Disney’s model train, “the Lilly Belle.” Later Disney and his wife, traveled to see Dali and his wife, Gala, at their home in Port Lligat, Spain.

“Destino” was finally finished in 2003 after Walt’s nephew, Roy, hired French director Dominique Monfery to complete what Dali left behind with the help of computers. Hench, then in his 90s, also helped animators figure out where Dali was initially headed with the story.

The adaptation includes Dali-sque images of plants with eyeballs, ants morphing into beret-wearing men on bicycles and a ballerina removing her head to throw at a baseball player wielding a bat.

“Destino” was nominated for an Academy Award in 2004 for best animated short film. Although it didn’t win, Nicolaou says the piece deserves recognition for “incrementally expanding our vision of who Walt Disney was.” -AP