I am rude to you in the queue for a bus because you, an old man, are not moving fast enough; I am quite avoidably rude to you, I am a reasonably civilized human being and know and believe that such rudeness is wrong and bad and unbecoming of humanity. I insatiate it nevertheless. But logically there is more to my rudeness than the weakness of the flesh which fails all too often to be in alignment with the knowledge of its own spirit.

In being rude to you I wordlessly yet loudly proclaim to the world both present and absent that one may be rude to another in my situation, that one-anyone-is permitted such rudeness. All free action, i.e., action not done under duress, is a proclamation of its permittedness, legitimacy, whatever retrospectively may be our reservations and regrets about it, for no man is under a law of freedom apart from all men.

Thus in being rude to you I say, without words, not only to onlookers but to all mankind-past, present and future mankind-that one may be rude in the way I am, that you may also be rude in the same way. So loud is this wordless permission that given, as the case in question assumes, my own belief in the wrongness of my rudeness, the following becomes the illogical testament of my wrongdoing: “I ought not to be rude to you in the given situation, but one is permitted such rudeness.”

The example I have chosen is an instance of mild moral evil with which we have all learned helplessly to live, but its self-contradiction is no less a stultification than the self-contradiction involved in genocide committed by a civilized nation or people, for in the latter case there is no more illogicality than that of believing something, e.g., genocide, to be wrong, and at the same time wordlessly implying its permittedness.

In all moral evil, great and small, merely irritating or unimaginably devastating, there is self-contradiction. And yet the embarrassment of such self contradiction does not much deter moral evil. Are we rational animals?

Why do we do moral evil, why do we involve ourselves in wrong-doing, in badness and abandonment of duty and inhumanity and insensitivity to man and life and nature?

It cannot be that the satisfactory general answer to this question is that we have unfulfilled desires for what worldliness has to offer us-name, fame, pleasures, sex, success, security, etc.-, the pain of unfulfillment driving us to wrongdoing, initially as well as vengefully.

Such an answer despite its prevalence and prestige is superficial and false because great and small immorality is committed often by the most materialistically fortunate human beings who have no want of worldly gifts and goods.

The satisfactory deep-going answer to the question as to why we do evil must be: we are not happy even with our happiness, there is not in our samsaric situatedness within and without ourselves any point of absolute rest and peace and uncheatable fulfillment. We are not joyously self situated in wisdom.

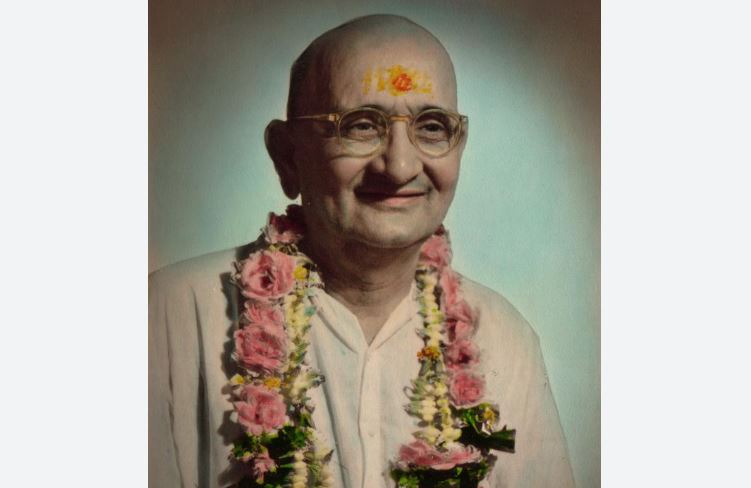

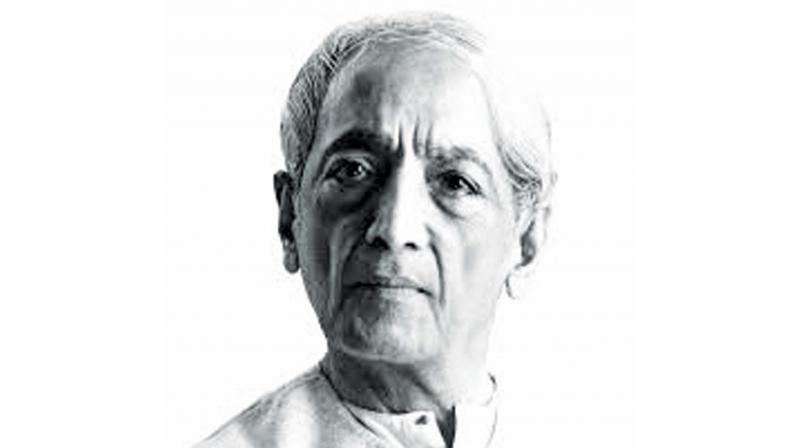

Writer, philosopher Ramchandra Gandhi (1937-2007) was a grandson of Mahatma Gandhi. Excerpted from ‘I am Thou, Meditations on the Truth of India’

Ramchandra Gandhi