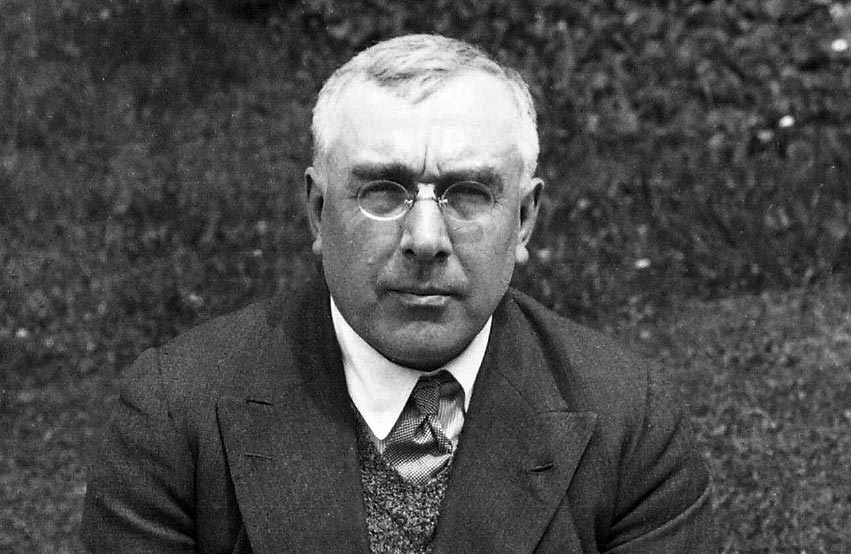

D. Ouspensky

The state in which we work, talk, imagine ourselves conscious beings and so forth — we ordinarily call ‘waking consciousness’ or ‘clear consciousness’ — but really it should be called ‘waking sleep’ or ‘relative consciousness’. In the state of sleep we can have glimpses of relative consciousness.

In the state of relative consciousness we can have glimpses of self-consciousness. But if we want to have more prolonged periods of self-consciousness and not merely glimpses, we must understand that they cannot come by themselves. They need will action.

This means that frequency and duration of moments of self-consciousness depend on the command one has over oneself. So it means too that consciousness and will are almost one and the same thing, or in any case, aspects of the same thing.

At this point it must be understood that the first obstacle in the way of the development of self-consciousness in man is his conviction that he already possesses self-consciousness, or at any rate that he can have it at any time he likes. It is very difficult to persuade a man that he is not conscious, and cannot be conscious, at will.

It is particularly difficult because here nature plays a very funny trick. If you ask a man if he is conscious, or if you say to him that he is not conscious, he will answer that he is conscious and that it is absurd to say that he is not, because he hears and understands you.

And he will be quite right, although at the same time quite wrong. This is nature’s trick. He will be quite right because your question or your remark has made him vaguely conscious for a moment. Next moment consciousness will disappear. But he will remember what you said and what he answered, and he will certainly consider himself conscious. In reality, acquiring self-consciousness means long and hard work.

How can a man agree to this work if he thinks he already possesses the very thing which is promised him as the result of long and hard work? Naturally a man will not begin this work and will not consider it necessary until he becomes convinced that he possesses neither self-consciousness nor all that is connected with it, that is to say, unity or individuality, permanent ‘I’ and will.

This is the chief point in work upon oneself. If one realizes that all the difficulties in the work depend on the fact that one cannot remember oneself, one already knows what one must do. One must try to remember oneself. In order to do this one must struggle with mechanical thoughts and one must struggle with imagination.

If one does this conscientiously and persistently one will see results in a comparatively short time. But one must not think that it is easy or that one can master this practice immediately. Self-remembering, as it is called, is a very difficult thing to learn to practice.

We cannot become conscious at will, at the moment when we want to, because we have no command over states of consciousness. And if we start remembering ourselves by the special construction of our thoughts, that is, by the realization that we do not remember ourselves; that no one remembers himself, and by realizing what this means, this realization will bring us to consciousness.

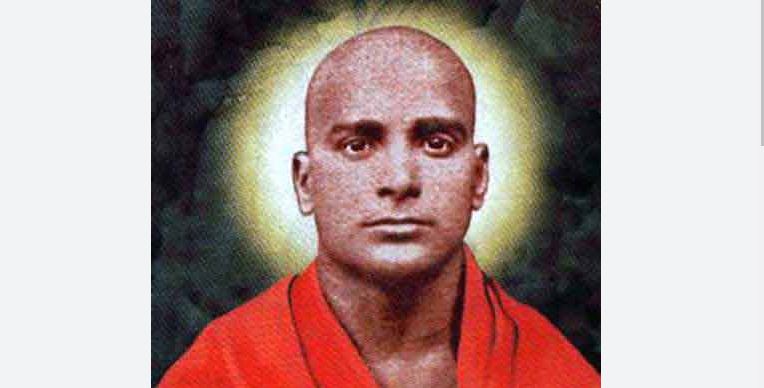

Excerpted from the book ‘Conscience.’ Pyotr Demianovich Ouspensky was a Russian esotericist known for his expositions of the early work of the Greek-Armenian teacher of esoteric doctrine George Gurdjieff. Ouspensky’s 142nd birth anniversary was observed on March 5.