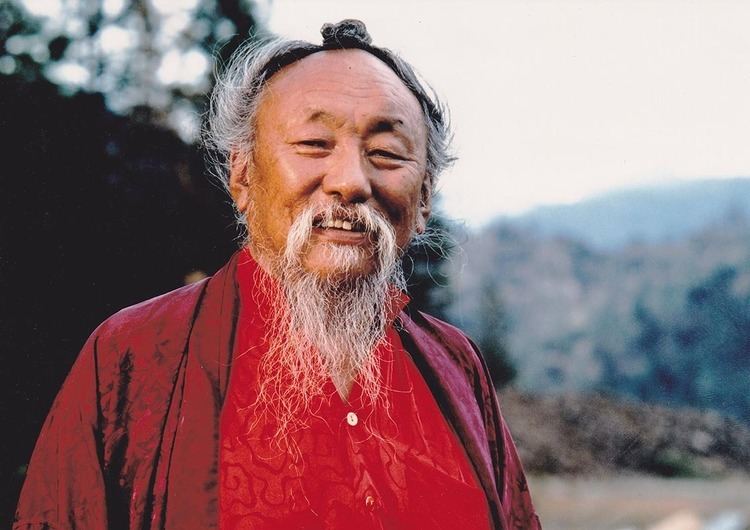

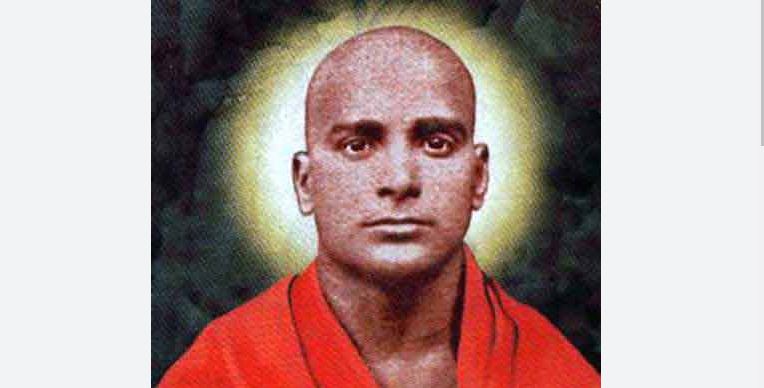

Chagdud Tulku Rinpoche

Why do we pray? We might think that if we do the Buddha, or God, or the deity will look kindly upon us, bestow blessings, protect us. We might believe that if we don’t, the deity won’t like us, might even punish us. But the purpose of prayer is not to win the approval or avert the wrath of an exterior God.

To the extent that we understand Buddha, God, the deity, to be an expression of ultimate reality, to that extent we receive blessings when we pray. To the extent that we have faith in the boundless qualities of the deity’s love and compassion, to that extent we receive the blessings of those qualities.

Sometimes we project human characteristics onto things that aren’t human. For example, if we sentimentally think, “My dog is meditating with me,” we’re only attributing that behavior to the dog; we’re imagining what it’s doing. When we anthropomorphize God, we project our own faults and limitations, imagining they’re God’s as well.

This is why many people believe that God either likes or dislikes them depending on their behavior. “I won’t be able to have this or that because God doesn’t like me—I forgot to pray.” Or worse, “If God doesn’t like me, I’ll end up in hell.”

If God feels happy or sad because we do or do not offer prayer, then God is not flawless, not an embodiment of perfect compassion and love. Any manifestation of the absolute truth, by its very nature, has neither attachment to our prayers nor aversion to our lack of them. Such attributes are projections of our own mind.

To understand how prayer works, consider the sun, which shines everywhere without hesitation or hindrance. Like God or Buddha, it continuously radiates all its power, warmth, and light without differentiation. When the earth turns, it appears to us that the sun no longer shines. But that has nothing to do with the sun; it’s due to our own position on the shadow side of the earth. If we inhabit a deep, dark mine shaft, it’s not the sun’s fault that we feel cold.

Or if we keep our eyes closed, it’s not the sun’s fault that we don’t see light. The sun’s blessings are all-pervasive, whether we are open to them or not. Through prayer, we come out of the mine shaft, open our eyes, become receptive to enlightened presence, the omnipotent love and compassion that exist for all beings.

Even if we aren’t familiar with the idea of praying to a deity, most of us feel the presence of some higher principle or truth—some source of wisdom, compassion, and power with the ability to benefit. Praying to that higher principle will without doubt be fruitful.

However, it is very important not to be small-minded in prayer. You might want to pray for a new car, but how do you know if a new car is what you need? It’s better to simply pray for what’s best, realizing that you may not know what that is.

We pray for what’s best not only for ourselves, but for all beings. When we’re just starting practice, our self-importance is often so strong that our prayers remain very selfish and only reinforce rather than transform self-centeredness. So until our motivation becomes more pure-hearted, it may be beneficial to spend more time cultivating loving kindness than praying.

Chagdud Tulku (1930–2002) was a teacher of the Nyingma school of Vajrayana Tibetan Buddhism. Excerpted from Tricycle: The Buddhist Review