Tarun Basu

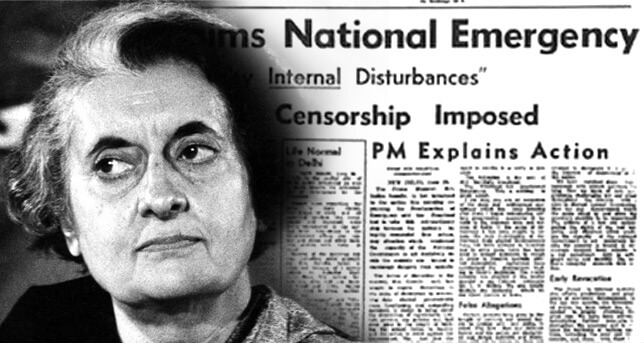

June 25-26 came and went all these years with hardly a ripple in Indian polity, save for a few reminiscent newspaper articles by a dying breed of journalists and politicians who lived through those momentous times. Two generations of Indians have grown into adulthood since Indira Gandhi, in a surreptitious midnight crackdown invoking the Maintenance of Internal Security Act (MISA) on June 25, 1975, curtailed fundamental rights, jailed political and other opponents of her rule and imposed press censorship in the enforcement of a declaration of internal emergency. Democratic India had not seen anything like this since British colonial rule and the next 19 months marked a watershed in the country’s checkered history.

For a rookie sub-editor working on late-night duty in the newsroom of the United News of India (UNI) news agency – that was least prepared for the news avalanche to follow post-midnight, -the period marked a loss of political innocence. The events are still too vivid – and in a way searing – in memory recesses to evade recall: the first startling reports of the closure of newspaper printing presses, switching off of power and seizure of newspapers from places as far apart as Jalandhar and Indore; sightings of unusual security movement at many places, including downtown Connaught Place in the capital; rumors of midnight arrests of opposition leaders, and then the first call from a leading opposition figure of his impending arrest.

Acting on a tip-off, a colleague, Arul Louis, who now lives in New York, and I – in the absence of any senior reporters at that hour – rushed to the nearby Parliament Street police station to get the latest information in an era where there were no mobile phones and landlines worked fitfully, if at all. It was past 2.30 a.m. and the city was asleep, blissfully unaware of the retributory machinations of a democratically elected prime minister, who was going to such lengths to subvert democracy, in order to trump an adverse judicial verdict holding her guilty of electoral malpractices.

Midnight swoops

Outside the sprawling white-colonnaded police station there was unusual activity at that hour and riot police were being driven out in police trucks. The air was taut with tension though no one would say anything. The two of us were asked to leave, but we hung on. The defiant wait proved journalistically rewarding as very soon a white Ambassador car drove in a flurry of escort vehicles. Wedged in between two plain clothed police officials was the familiar sight of Jayaprakash Narayan, hailed as “Lok Nayak”, or a people’s leader, who the day before had given a call to the military at a massive public rally in Delhi to act on their conscience and revolt and called for Mrs. Gandhi’s resignation.

As the tough-looking cops tried to shield the frail, gangling man, Narayan gave his terse reaction with words that were to make history: “Vinash kale vipreet buddhi” (madness takes hold as the end nears). We rushed back to our office to file the breaking news.

From then on the few of us who were privileged to be on the nocturnal beat worked feverishly to a climactic dawn. With the printed phone book on our laps, every opposition leader worth his salt was rung up at that hour, from the secluded confines of then UNI General Manager G. G. Mirchandani’s room, and the tracking efforts proved rewarding. Mirchandani, though a former government information official, encouraged us to keep the truth flowing and the public informed till government censors came in the morning and took over the editorial operations.

Aides of Moraraji Desai, who was to later become the prime minister in 1977, heading a short-lived government, said he had been woken in bed by police and was being taken to jail. Similar stories were heard from the homes of Atal Bihari Vajpayee, Chandra Shekhar, Charan Singh, all of who were to become prime ministers of India. Sikander Bakht, who later became a cabinet minister in the Desai government and was one of the stalwarts of the Jana Sangh/BJP, said he had hidden in his bathroom when the police came calling and appealed to us to save him from arrest.

Tales of midnight knocks and police swoops on homes of targeted people came from around the nation as every conceivable opponent of the then prime minister was rounded up and thrown into prison cells.

A few, like Subramanian Swamy, were tipped off by colleagues and escaped in time, catching the first flights to the freedom of the West from where they organized opposition to the repressive regime. Dissenting teachers, students, journalists, intellectuals were all put behind bars as India experienced for the first time living in an authoritarian system. The crackdown came a little later on newspapers and news agencies as authorities belatedly realized what havoc it had caused in disseminating information about the crackdown that, in the pre-internet era, would otherwise have been imposed swiftly, silently in the dead of the night away from prying journalistic eyes.

Triumph of democracy

The Emergency rule made heroes of some but revealed the clay feet of most. Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) leader L. K. Advani, then leader of the forerunner Jana Sangh party, made the telling comment later on subservience when he said that people when they were asked to bend ended up crawling. The remarks applied to journalists, officials, industrialists, and all those who displayed a singular lack of spine in standing up to Mrs. Gandhi’s dictatorship and instead ended singing paeans to her virtues lest they also were arrested.

It is said charitably by many historians that it was a tribute to the innate democratic spirit of Indira Gandhi, as the daughter of Jawaharlal Nehru, that she decided to lift the Emergency after 21 months and ordered free elections in the hope that people would endorse her move. But the truth was that her own intelligence reports told her about the flourishing underground movement against the Emergency that could pose a threat to her life, as that of her upstart son Sanjay Gandhi; the gross abuses of power by police and other regulatory officials like demolition of slums and forcible sterilization; the widespread criticism abroad, particularly the West, and finally, the realization that the Indian people can be gagged but their inborn democratic spirit can never be crushed.

The elections that followed in March 1977 were a fitting riposte to her and Sanjay Gandhi’s political calculations. There was an element of utter disbelief when results showed that Mrs. Gandhi, her son, her acolytes, and countless cheerleaders had all been routed. The repressive regime went but the scars it left took a long time to heal and in some cases caused lasting damage to the body politic. The credibility of the vital pillars of the nation, like the judiciary, stood badly eroded, corruption became institutionalized in the name of party mobilization, and politics became the last refuge of the criminalized and the lumpen as long as they served its political ends.

Emergency’s lessons

It is often said by elite apologists of the Emergency that it was only then that trains ran on time, discipline became the watchword in public life and the all-pervading fear of police kept down urban crime. But all such intellectual sophistry can easily be punctured by democratic paradigms where all these and much more can be achieved by more accountability of the rulers and a sense of responsibility in the ruled.

That fateful March 1977 election vindicated Indian democratic traditions and proved the triumph of freedom over bread. Ballot after regular ballot has shown that just because a man is poor and maybe cannot read does not mean he does not care for his liberty and human rights. It went to show that democracy and freedom of choice was very much an Indian value, perhaps more ancient and durable than traditions in Britain, where parliamentary democracy is said to have originated.

It may be difficult for another prime minister to impose Emergency under similar circumstances because of a constitutional amendment in 1978. But whether the lessons it taught to the ruler and the ruled are still remembered remains doubtful. Many of the repressive traits of the Emergency can be seen even now in the way dissent is sought to be crushed and civil liberties curtailed, or in the way some key pillars of democracy show compliant and craven behavior without possibly even being asked to do so. South Asia Monitor