Sunthar Visuvalingam

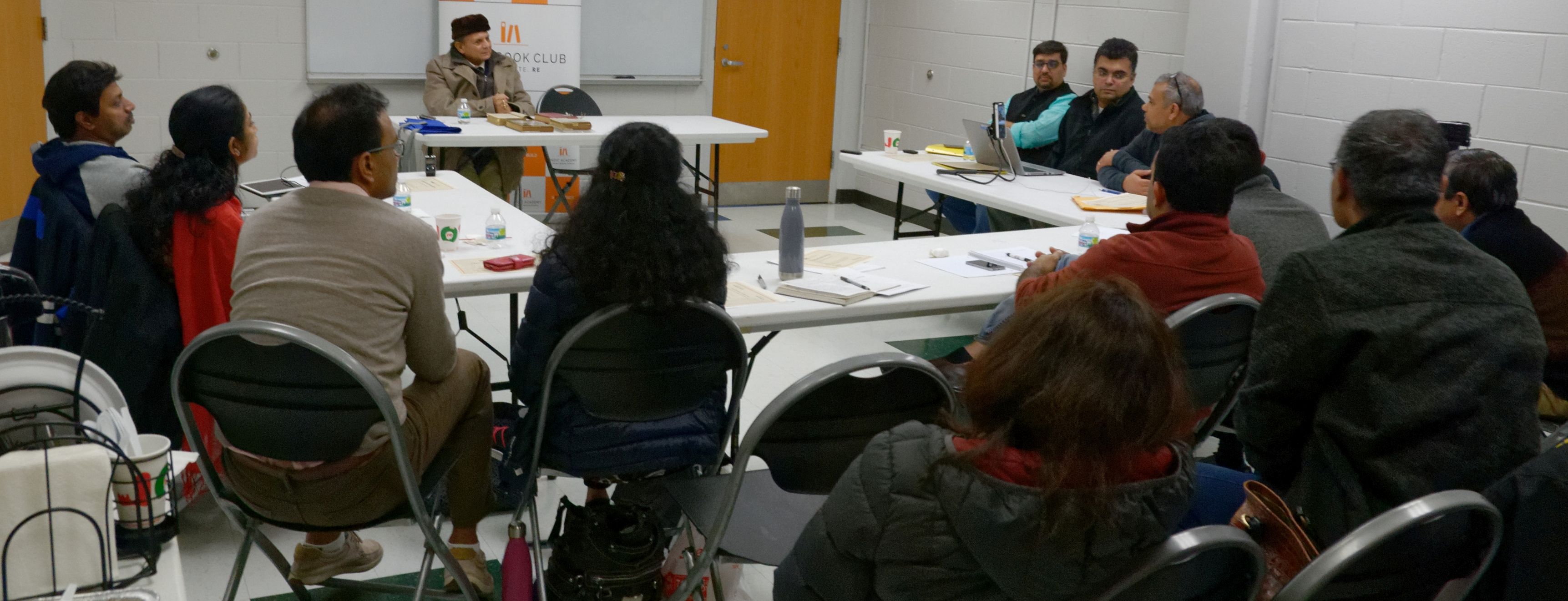

CHICAGO: Hosted by Indic Academy, educationist Bharat Gupt conducted a four-hour leadership workshop at Palatine Park District Community Center on December 15 seeking to familiarize young Hindu adults with their traditional value-system.

The exposition was on the basis as crystallized in the authoritative treatises (shastra) on socioreligious order (dharma), political economy (artha) and the pursuit of pleasure (kama). In the popular mind, Kamasutra has been reduced to sexual acrobatics, Artha-shastra to Machiavellian intrigues, Manu-Smriti to caste oppression.

A civilization, he insisted, lives and reproduces itself through such foundational texts that in India over the last 150 years have become targets of castigation and ridicule. Instead of constantly being “apologetic” in the face of outside and modern criticisms, we need to “stand by, investigate and have faith (shraddha) in the (diversified) tradition (veda-mata),” based on reason and especially (direct) experience.

Given the (medieval and Western) over-emphasis on world-renunciation and spiritual transcendence (moksha) as the distinctive summum bonum of Indic civilization, Gupt deliberately focused on these three this-worldly pursuits (tri-varga). Through the performing arts, the terminology and complex concepts (e.g. rasa) enshrined in these classical texts have permeated Indic society to become the common parlance of even illiterate folks.

Gupt began by emphasizing that the ancient hierarchical order (varna) had to be understood in relation to the four stages of life (ashrama), viz. student, householder, retirement, and renunciation. Whereas disciplined indulgence in sexual pleasure (unblemished by sinfulness) was expected of the householder, celibacy (brahmacharya) for example was prescribed only for the other stages. Though people were generally proud of their inherited caste, there was historically attested (especially group) mobility, both upward and downward, imposed by circumstance or inclination.

The generation, preservation and transmission of knowledge assured the brahmin’s immunity at the top of the hierarchy.Responsible for curriculum and legislation, they were consequently consigned to a life of austerity, especially stringent for those most engaged with Vedic tradition. Excellence was likewise aimed by and expected of each caste in conformity with life-station from early youth. Society reigned over state.

Doniger’s latest book titled Against Dharma aims to demonstrate that the “subversive” brahmin authors of the ‘normative’ treatises on artha, kama, etc., were attempting to debunk the overarching system of ethics. While partly acknowledging her claim that modern Hindu attitudes to carnal enjoyment have been unduly constricted by Victorian puritanism, Gupt, noted that this had been largely imposed by British colonial governance. He nevertheless sought to distinguish the classical celebration of sex from the ravages of Freudianism, gender-conflict and contemporary permissivity.

Against her portrayal of Vatsyayana as an “anti-Manu” atheist, Gupt sought to demonstrate how Kamasutra’s opening declaration of integrating the (hedonistic) pursuit of pleasure into a balanced pursuit of the purusharthas was not mere lip service. Just as treatises on dharma allow for transgressions under dire circumstances, so too those on kama allow for diverse psychophysical needs, thereby confirming that Hindu morality is not black-and-white but graded and conditionally complex. They not only prescribe the manifold (seductive) arts of the courtesan but the lifelong education of the marriageable woman.

Enjoying the personal freedoms and legal equality in the US inculcated as universal norms by Western education, poses challenges to understanding—let alone accepting—ancient monarchy (‘tyranny’), subordination of women (‘patriarchy’) and especially (birth-based social) hierarchy (‘exploitation’). So much so that several in the audience—especially those exposed to Chinmaya Mission teachings from the Bhagavad Gita—repeatedly interrupted to argue that caste-status was determined by one’s innate tendencies (guna).

That Gupt hails from a merchant (vaishya) family or that I, an accredited Sanskritist interpreting Vedic texts and traditions, am of ‘low-birth’ (shudra), would lend credence to such claims that profession was originally or ideally determined by innate aptitude and inclination rather than birth.Gupt however argued, correctly, that it was anachronistic to apply contemporary notions of (individual) ‘freedom’ to ancestors who sought to excel at hereditary occupations taken for granted.

Even now, long after the workshop, links and articles keep being posted at its associated WhatsApp group invoking, for example, the publications of professor Balagangadhar and his research team that claim that caste remains an (unwitting) invention of the Western colonial gaze. Due to the interruptions, Gupt could not do justice to Artha-Shastra within his remaining five minutes. Pedagogically, it might have been preferable to restrict questions till after each (legitimate) ‘life-pursuit’ (purushartha) had been expounded or adopt the completely different approach of introducing the ancient treatises by systematically questioning our contemporary, largely unconscious, premises on ‘universal’ values.

He had to do this anyway, but as ad hoc digressions in response to persistent doubts. Forming a new generation of leaders is not simply to pump them with (half-digested) quotes from ‘antiquated’ texts but to help them think through and appropriate their vision in the manner exemplified by the teacher.

Video recording of Gupt’s talk interspersed with Q&A is accessible