Zen is extremely elusive as far as its outward aspects are concerned; when you think you have caught a glimpse of it, it is no more there; from afar it looks so approachable, but as soon as you come near it you see it even further away from you than before.

Unless, therefore, you devote some years of earnest study to the understanding of its primary principles, it is not to be expected that you will begin to have a fair grasp of Zen.

“The way to ascend unto God is to descend into one’s self”; – these are Hugo’s words. “If thou wishest to search out the deep things of God, search out the depths of thine own spirit”; – this comes from Richard of St. Victor.

When all these deep things are searched out there is after all no “self” where you can descend, there is no “spirit”, no “God” whose depths are to be fathomed. Why? Because Zen is a bottomless abyss.

Zen declares, though in somewhat different manner: “Nothing really exists throughout the triple world; where do you wish to see the mind (or spirit, *hsin*)? The four elements are all empty in their ultimate nature; where could the Buddha’s abode be? – but lo! the truth is unfolding itself right before your eye.

This is all there is to it – and indeed nothing more!” A minute’s hesitation and Zen is irrevocably lost. All the Buddhas of the past, present, and future may try to make you catch it once more, and yet it is a thousand miles away. “Mind-murder” and “self-intoxication”, forsooth! Zen has no time to bother itself with such criticisms.

Zen is the spirit of a man. Zen believes in inner purity and goodness. Whatever is superadded or violently torn away, injures the wholesomeness of the spirit.

The basic idea of Zen is to come in touch with the inner workings of our being, and to do so in the most direct way possible, without resorting to anything external or superadded.

Therefore, anything that has the semblance of an external authority is rejected by Zen. Absolute faith is placed in a man’s own inner being. For whatever authority there is in Zen, all comes from within. This is true in the strictest sense of the word. Even the reasoning faculty is not considered final or absolute. On the contrary, it hinders the mind from coming into the directest communication with itself.

The intellect accomplishes its mission when it works as an intermediary, and Zen has nothing to do with the intermediary except when it desires to communicate itself to others. For this reason all the scriptures are merely tentative and provisory; there is in them no finality. The central fact of life as it is lived is what Zen aims to grasp, and this in the most direct and most vital manner.

Zen professes itself to be the spirit of Buddhism, but in fact it is the spirit of all religions and philosophies. When Zen is thoroughly understood, absolute peace of mind is attained, and a man lives as he ought to live.

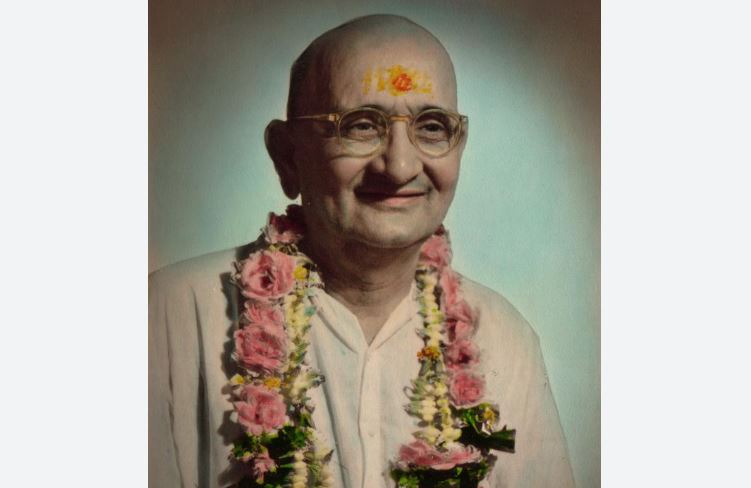

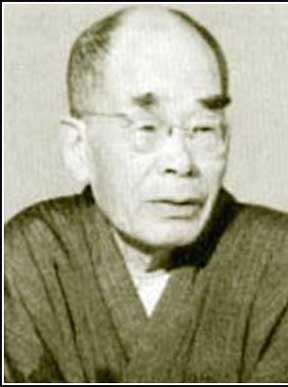

From An Introduction to Zen Buddhism. D.T. Suzuki, was a Japanese author instrumental in spreading interest in Zen and Shin to the West.

D.T. Suzuki