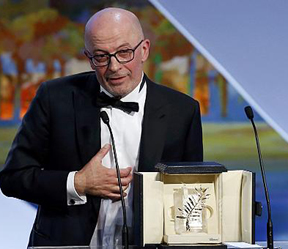

In Cannes, everyone had a prediction as to what would win, but the winner turned out to be a film that nobody predicted: Jacques Audiard’s Dheepan, the gritty, powerful story of a Tamil guerrilla, a young woman, and a girl who pretend to be a family so they can leave the terrifying violence of war-torn Sri Lanka and settle in supposedly civilized France-only to find themselves in a

housing project filled with drug dealers packing guns.

It’s a good, intelligent, finely directed film that seemed, in the crazy logic of Cannes where people want masterpieces, to be merely a good, intelligent finely directed film. The jury clearly thought it better than that, and Audiard, a consistently interesting and excellent director of the old school has won the Palme he’s been heading for over the past twenty years.

The Dark Horse Winner: Rooney Mara

From the moment Carol screened early in the festival, it was almost an article of faith that the Best Actress prize would go to Cate Blanchett for her emblematic portrait of the title character, a well-off, well-turned-out fifties wife who begins a love affair with a young department saleswoman played by Rooney Mara. Only a handful ventured the opinion that, in fact, Mara was actually better than Blanchett because her performance lets us in rather than locks us out. Turns out the jury agreed.

The Winning Future: Young Directors

Three awards went to comparative newcomers. Best Screenplay went to Chronic, a bleak story about a nurse by the Mexican director Michel Franco. The Jury Prize went to Yorgos Lanthimos’s amusingly offbeat comedy The Lobster with Colin Farrell and Rachel Weisz. And the Grand Prix (basically second place) went to Laszlo Nemes for Son of Saul, a harrowing story about a Jewish prisoner forced to help the Nazis with the running of a death camp. Directed with astonishing force, it flings you into the middle of horrible things.

The Winning Tongue: France

In a festival filled with English-speaking movie actors starring in movies by directors whose first language isn’t English, the best acting prizes (and the Palme d’Or) went to people speaking French.

The Best Actor was Vincent Lindon from the film The Measure of a Man, a superbly turned story of a factory worker who loses his job and finds himself thrown onto the mercies of the market for labor-he winds up as a security guard.

Possessed with one of those great, un-pretty Gallic actor faces and an unshakeable air of manliness, Lindon gives a watchful performance that’s rivetingly deep without ever being flashy. As if that weren’t enough, Rooney wound up sharing the Best Actress prize with Emmanuelle Bercot, the French star of Mon Roi, a juicy, crazy romantic nightmare in which her character falls in love with a sexy, charismatic man (Vincent Cassel) who turns out to be-you guessed it-sexy, charismatic trouble.

If Lindon’s performance is impressive for its restraint, Bercot’s is exciting for its absence. She laughs, she cries, she strips, she has a baby, she laughs and cries some more-oh yes, she’s also a lawyer.

More than a Prize

Cannes screenings don’t get more hushed than during the premiere of Hou Hsiao-hsien’s The Assassin, the story of a female assassin (gorgeous Shu Qi) during the Tang Dynasty of the ninth century. While the movie is slow and at moments baffling, it is also one of the most staggeringly exquisite films.

It featured the festival’s most beautiful actress among the most beautiful cast wearing the most beautiful costumes in the most beautiful settings shot in the most beautiful light imaginable. So why didn’t it win? The short answer is that it’s simply too refined-too rarefied-to win over the majority of any group, including a sophisticated Cannes jury. Still, the jury knew that The Assassin is something astonishing, which is why they gave Hou the Best Director prize. It was the least they could do for a film whose level of artistry outstripped everything else in the competition.