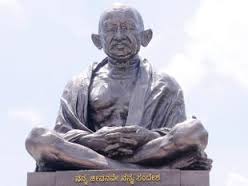

NEW DELHI: The Mahatma Gandhi bequeathed by history is a watered-down, saccharine version of the original man, claims a new book which talks of what he really stood for.

NEW DELHI: The Mahatma Gandhi bequeathed by history is a watered-down, saccharine version of the original man, claims a new book which talks of what he really stood for.

In “What Gandhi Says,” American political scientist and author Norman G Finkelstein draws on extensive readings of Gandhi’s oeuvre to set out the basic principles of his approach as well as to argue that it had contradictions and limitations.

“He is the saintly, other-worldly eccentric who would not hurt a fly, and looked as if he could not even if he were so inclined,” he writes.

The author dubs Gandhi as the shrewdest of political tacticians “who could gauge better than any of his contemporaries the reserves and limits of his people and his adversaries.”

He says the real Gandhi did loathe violence but he loathed cowardice more than violence.

“If his constituents could not find the inner wherewithal to resist non-violently, then he exhorted them to find the courage to hit back those who assaulted or demeaned them,” the book, published by Fingerprint, says.

According to Finkelstein, if Gandhi preached simultaneously the virtues of non-violence and courage, it was because he believed that non-violence required more courage than violence.

“Those who used non-violence not to resist but instead as a pretext to flee an assailant were, according to Gandhi, the most contemptible of human creatures, undeserving of life,” he says. The author first began to read Gandhi a few years ago in order to think through a non-violent strategy for ending the Israeli occupation of Palestinian land.

“But the field for the application of Gandhi’s ideas has now been vastly expanded by the emergence of the Arab Spring and non-violent resistance movements around the world.

Gandhi’s name is everywhere on the lips of those challenging a political system that shuts out the overwhelming majority of people and an economic system that leaves them futureless.

“In my own city of New York, the idea of non-violent civil disobedience has seized the imagination of young people and energized them with the hope that they can bring even the ramparts of Wall Street tumbling down,” he says.

He asserts that a new generation is now experimenting with and envisioning novel ways of living, and pondering how to redistribute power and eliminate privilege. The life experience and reflections of Gandhi provide a rich trove to help guide these idealistic but disciplined, courageous but cautious youth as they venture forth to create a brighter future.

The author also talks about Gandhi’s concept of Satyagraha.

“Unlike violence, which ‘obtains reforms by external means’, Satyagraha, according to Gandhi, relied exclusively on the internal method of self-suffering: ‘the more innocent and pure the suffering the more potent will it be in its effect’,” he writes.

The author also claims that Gandhi was not a pacifist, believed in the right of those being attacked to strike back and regarded inaction as a result of cowardice to be a greater sin than even the most ill-considered aggression.

He says it was never quite clear whom Gandhi was trying to reach with his non-violent resistance.

“Sometimes he spoke about wanting to melt even (Adolf) Hitler’s heart,” he writes. -PTI