Safransky: Let’s pretend that I’m thoroughly unfamiliar with contemporary spiritual vocabularies. How would you describe your teaching to me?

Adyashanti: My background is primarily Zen Buddhism, and yet I would not describe what I teach as Zen. I don’t really see myself as transmitting any particular tradition. My teaching has to do with enlightenment, with awakening to what you really are. It does not matter to me anymore whether I use Buddhist vocabulary, or Christian vocabulary, or Hindu vocabulary. Any vocabulary will do.

The heart of my teaching is to help people question their argument with reality, with what is, and also to help them question their whole notion of themselves.

Saunders: Do you use the terms “awakening” and “enlightenment” interchangeably, or are you talking about two different experiences?

Adyashanti: Awakening is when you realize that what you thought you were was nothing more than a dream, and you perceive the reality outside the dream, what’s dreaming the dream of you. It’s not just a mystical experience. It is actually realizing the underlying unity of all things.

Simply because you’ve had an awakening, however, does not mean you stay awake. Enlightenment, in simple terms, is when you stay awake. If the awakening is abiding, that’s enlightenment. And most awakenings are not abiding – at least, not initially.

Saunders: Awakening and enlightenment sound like head-bound or heart-bound concepts.

Adyashanti: Enlightenment has nothing to do with the head or the heart. Certainly, the head and the heart tend to open up, but that’s a byproduct. Enlightenment is actually waking up from the head and from the heart. It’s waking up from the dream of “me” and seeing the oneness of all things.

That’s what I mean by “reality”: that oneness. The truth is that you are that unity. You are not simply a particular person in a particular body with a particular personality; you are that one reality, which manifests itself as all these seemingly separate things.

Saunders: Are the body and physical sensations illusory?

Adyashanti: Yes and no. Ultimately, everything’s a dream, and yet you still have to deal with the body. It’s still there. You can call it “a dream,” but it’s still going to hurt if you bump your head.

Safransky: Most traditions suggest that years of spiritual practice are necessary before one becomes enlightened, but you say that it’s a mistake to look to the future, to see spiritual awakening as some kind of goal.

Adyashanti: One of the best ways to avoid awakening is to let the idea of awakening be co-opted by the mind and then projected onto a future event: something that’s going to happen outside of this moment.

Of course, something may happen in the next moment – something’s always happening in the next moment – but the truth lies right here and right now; it is right here and right now. This looking to the future isn’t really the fault of the spiritual practices themselves; it’s the attitude with which the mind engages in the practices – an attitude that is seeking a future end and seeing that end as somehow inherently different from what already exists here and now.

The role of the spiritual practice is basically to exhaust the seeker. If the practice does what it’s supposed to do, it exhausts our energy for seeking, and then reality has a chance to present itself. In that sense, spiritual practices can help lead to awakening. But that’s different from saying that the practice produces the awakening.

The spiritual practitioner is like someone who’s running and is really tired and wants to rest. You could say, “Well, just stop, then.” But they have this idea that they have to cross a finish line before they can stop. If you can convince them that they can just stop, they’ll be amazed.

Excerpted from an interview with Adyashanti in thesunmagazine.org

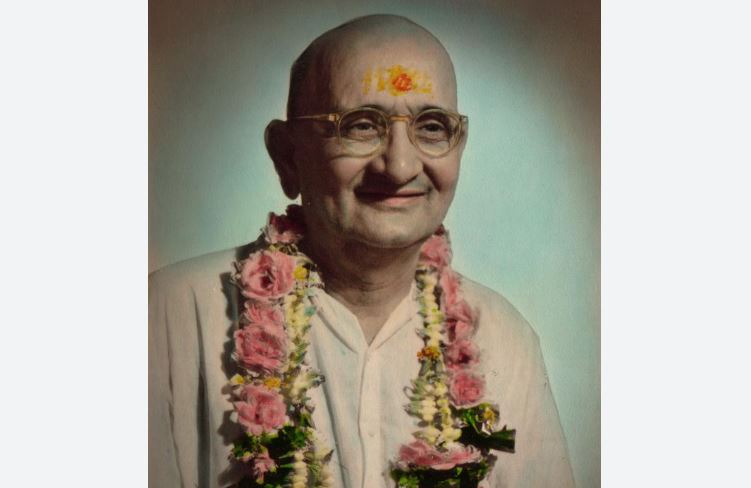

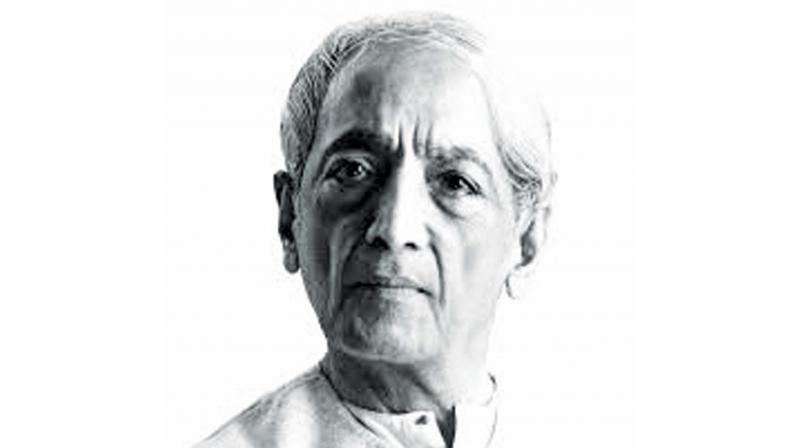

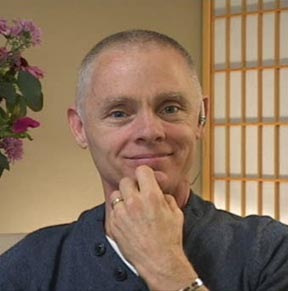

Adyashanti