AROONIM BHUYAN & CAPT KRISHAN SHARMA

India Post News Service

India’s share of the world economy when Britain arrived on its shores was 23 per cent. By the time the British left, it was down to below 4 per cent. This was simply because India had been governed for the benefit of Britain.

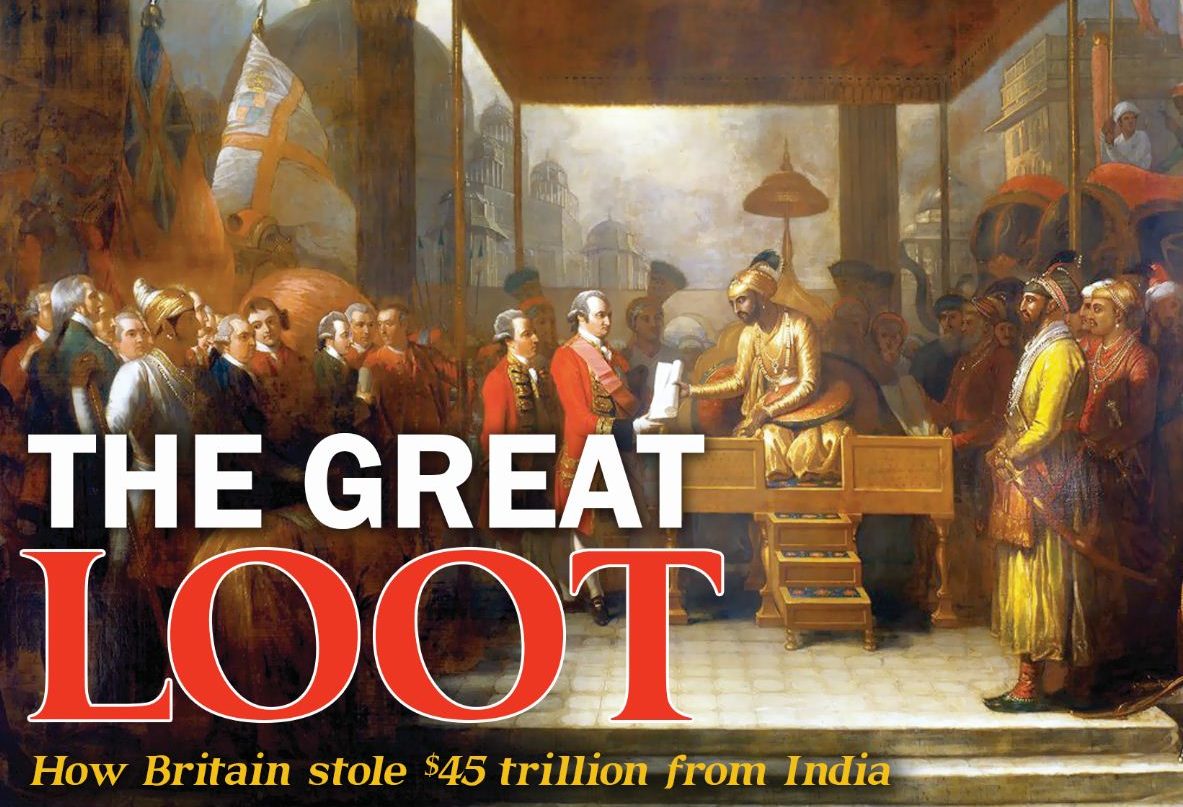

Colonialists like Robert Clive brought their rotten boroughs in England on the proceeds of their loot in India while taking the Hindi word loot into their dictionary as well as their habits, Congress MP Shashi Tharoor had said at a debate organized by the Oxford Union a couple of years back.

British colonialism of India started with the entry of the East India Company, which was founded in 1600 as The Company of Merchants of London Trading into the East Indies. It gained a foothold in India with the establishment of a factory in Masulipatnam on the eastern coast of India in 1611 and the grant of the rights to establish a factory in Surat in 1612 by the Mughal emperor Jahangir. In 1640, after receiving similar permission from the Vijayanagara ruler farther south, a second factory was established in Madras (now Chennai) on the southeastern coast. Bombay island, not far from Surat, a former Portuguese outpost gifted to England as dowry in the marriage of Catherine of Braganza to Charles II, was leased by the Company in 1668. Two decades later, the Company established a presence on the eastern coast as well; far up that coast, in the Ganga river delta, a factory was set up in Calcutta. Since, during this time other companies – established by the Portuguese, Dutch, French, and Danish – were similarly expanding in the region, the English company’s unremarkable beginnings on coastal India offered no clues to what would become a lengthy presence on the Indian subcontinent.

There is a story that is commonly told in Britain that the colonisation of India – as horrible as it may have been – was not of any major economic benefit to Britain itself. If anything, the administration of India was a cost to Britain. So the fact that the empire was sustained for so long – the story goes – was a gesture of Britain’s benevolence.

Research by renowned economist Utsa Patnaik made public last year deals a crushing blow to this narrative. Drawing on nearly two centuries of detailed data on tax and trade, Patnaik calculated that Britain drained a total of nearly $45 trillion from India at today’s value.

“It’s a staggering sum. For perspective, $45 trillion is 17 times more than the total annual gross domestic product of the United Kingdom today,” Jason Hickel, an academic at the University of London and a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts, wrote in an article for Aljazeera.com in December 2018.

In a speech organized by the Atlantic Council in Washington last month, Indian External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar also reiterated this saying that the British took out of India $45 trillion at today’s value.

It happened through the trading system. Prior to the colonial period, Britain bought goods like textiles and rice from Indian producers and paid for them in the normal way – mostly with silver – as they did with any other country. But something changed in 1765, shortly after the East India Company took control of the subcontinent and established a monopoly over Indian trade.

Here’s how it worked. The East India Company began collecting taxes in India, and then cleverly used a portion of those revenues (about a third) to fund the purchase of Indian goods for British use. In other words, instead of paying for Indian goods out of their own pocket, British traders acquired them for free, “buying” from peasants and weavers using money that had just been taken from them.

It was a scam – theft on a grand scale. Yet most Indians were unaware of what was going on because the agent who collected the taxes was not the same as the one who showed up to buy their goods. Had it been the same person, they surely would have smelled a rat.

Some of the stolen goods were consumed in Britain, and the rest were re-exported elsewhere. The re-export system allowed Britain to finance a flow of imports from Europe, including strategic materials like iron, tar and timber, which were essential to Britain’s industrialisation. Indeed, the Industrial Revolution depended in large part on this systematic theft from India.

On top of this, the British were able to sell the stolen goods to other countries for much more than they “bought” them for in the first place, pocketing not only 100 percent of the original value of the goods but also the mark-up.

After the British Raj took over in 1858, colonizers added a special new twist to the tax-and-buy system. As the East India Company’s monopoly broke down, Indian producers were allowed to export their goods directly to other countries. But Britain made sure that the payments for those goods nonetheless ended up in London.

Britain didn’t develop India. Quite the contrary – as Patnaik’s work makes clear – India developed Britain.

Pitt’s India Act of 1784 gave the British government effective control of the private company for the first time. The new policies were designed for an elite civil service career that minimized temptations for corruption. Increasingly Company officials lived in separate compounds according to British standards. The Company’s rule lasted until 1858, when it was abolished after the Indian rebellion of 1857. With the Government of India Act 1858, the British government assumed the task of directly administering India in the new British Raj.

The greatest example of the British loot of India was the Kohinoor diamond, which is today a part of the British crown jewels.

Probably mined in Kollur Mine in India, there is no record of its original weight – but the earliest well-attested weight is 186 old carats (191 metric carats or 38.2 g). It changed hands between various factions in south and west Asia, until being ceded to Queen Victoria after the British annexation of the Punjab in 1849.Prince Albert, husband of Queen Victoria, ordered it to be re-cut as an oval brilliant. Brilliant-cut diamonds usually have 58 facets, but the Kohinoor has eight additional “star” facets around the culet, making a total of 66 facets.The much lighter but more dazzling stone was mounted in a honeysuckle brooch and a circlet worn by the queen.

Although Victoria wore it often, she became uneasy about the way in which the diamond had been acquired. In a letter to her eldest daughter, Victoria, Princess Royal, she wrote in the 1870s: “No one feels more strongly than I do about India or how much I opposed our taking those countries and I think no more will be taken, for it is very wrong and no advantage to us. You know also how I dislike wearing the Kohinoor”.

The great loot of India by the British also had an America connect – the Yale University. Originally known as the “Collegiate School”, the institution opened in the home of its first rector, Abraham Pierson, today considered the first president of Yale. Pierson lived in Killingworth (now Clinton). The school moved to Saybrook and then Wethersfield. In 1716, it moved to New Haven, Connecticut.

In 1718, Cotton Mather, son of Increase Mather,the sixth president of Harvard University, contacted the successful Boston born businessman Elihu Yale to ask him for financial help in constructing a new building for the college. Through the persuasion of Jeremiah Dummer, Elihu Yale, who had made a fortune through trade while living in Madras (now Chennai) as a representative of the East India Company, donated nine bales of goods, which were sold for more than 560 pounds, a substantial sum at the time. Cotton Mather suggested that the school change its name to “Yale College”.

And the loot continued as also the de-industrialization of India. Among the first Indian industries to be hit was textile.

The British generally wore clothes made up of either wool or leather even in summer. When Indian cotton clothes were introduced to them, they found it to be comfortable to wear in summer, it gained popularity among common people.

Imposition of taxes, banning of Indian textiles in other markets and physically abuse of Indian weavers by the British colonialists caused the death of Indian small scale textile industries. As Indian industries declined, British started selling their textiles in Indian markets too.

“The handloom weavers for example famed across the world whose products were exported around the world, Britain came right in,” Tharoor said in his speech at Oxford.

“There were actually these weavers’ making fine muslin as light as woven wear, it was said, and Britain came right in, smashed their thumbs, broke their looms, imposed tariffs and duties on their cloth and products and started, of course, taking their raw material from India and shipping back manufactured cloth flooding the world’s markets with what became the products of the dark and satanic mills of the Victoria in England.”

The extent of the great loot of India by the British can be gauged from the fact that colonialists even planned to dismantle the Taj Mahal and sell off its marbles.

“Since the British rule of India, Taj Mahal has encountered numerous threats. Lavish carpets, jewels, silver doors, and tapestries with which the Taj once adorned, were looted by the British along with local people,” the tajmahal.org.uk website states.

“In 1830, it even faced demolition when a crew led by the governor of India Lord William Bentinck was up and ready to begin the demolition work and auction off the marble, only to be stopped because he failed to make the scheme financially viable as no prospective buyers could be found.”

Following the abolition of slavery, the British took Indians as indentured labourers to work in sugarcane plantations in faraway lands like Caribbean, Fiji and Mauritius. Not only abroad deployed Indians in India itself as indentured labour like the workers of tea gardens in Assam. These people today are the descendants of tribals and backward castes brought by the British colonial planters as indentured labourers from the predominantly tribal and backward caste dominated regions of present-day Jharkhand, Odisha, Chhattisgarh, West Bengal and Andhra Pradesh into colonial Assam during 1860-90s in multiple phases for the purpose of being employed in the tea gardens industry as indentured labourers.

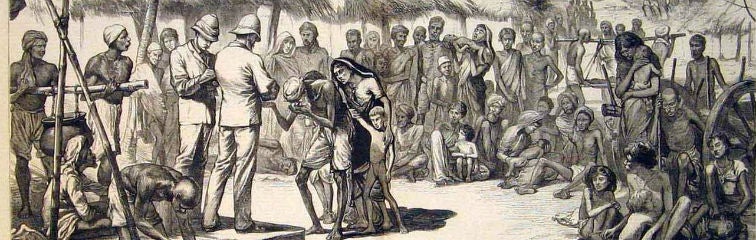

The British rulers also induced famines that led to the deaths of millions of Indians.

“The most famous example was, of course, was the great Bengal famine during the World War II when four million people died because Winston Churchill deliberately as a matter of written policy proceeded to divert essential supplies from civilians in Bengal to sturdy tummies and Europeans as reserve stockpiles,” Tharoor said in his speech.

“He said that the starvation of anyway underfed Bengalis mattered much less than that of sturdy Greeks’ – Churchill’s actual quote. And when conscious stricken British officials wrote to him pointing out that people were dying because of this decision, he peevishly wrote in the margins of file, ‘Why hasn’t Gandhi died yet?’”

The tale does not end there. In the World Wars I and II, the British deployed Indian soldiers to fight on their behalf.

According to Tharoor, one-sixth of all the British forces that fought in World War I were Indian – 54,000 Indians actually lost their lives in that war, 65 000 were wounded and another 4000 remained missing or in prison.

“Indian taxpayers had to cough up a 100 million pounds in that time’s money. India supplied 17 million rounds of ammunition, 600,000 rifles and machine guns, 42 million garments were stitched and sent out of India and 1.3 million Indian personnel served in this war,” he said and added that the cost was even higher during World War II in which around 2.5 million Indians were in uniform.

Of Britain’s total war debt of 3 billion pounds in 1945 money, 1.25 billion was owed to India and never actually paid, Tharoor stated. And as Patnaik’s research found out, it is worth $45 trillion in today’s money. Should Britain, repay, apologize or prepare for reparations?

“We need to recognize that Britain retained control of India not out of benevolence but for the sake of plunder and that Britain’s industrial rise didn’t emerge sui generis from the steam engine and strong institutions, as our schoolbooks would have it, but depended on violent theft from other lands and other peoples,” Hickel stated in his 2018 article

And therein is the tale of the great loot of India by the British! The Kohinoor diamond, statues from temples, and treasures from heritage sites stolen by British collectors and the Crown should be returned with dignity to the rightful owner – India.

(With inputs from Shashi Tharoor’s speech at the Oxford Union debate in May 2017 and Jason Hickel’s article in Aljazeera.com in December 2018.)