Justice prevails after centuries of destruction by invaders

AROONIM BHUYAN & CAPT. KRISHAN SHARMA

Closing a decades-old dispute, India’s Supreme Court ruled November 9 that a temple be built at the site where a mosque was constructed over what was Hindu deity Lord Rama’s birthplace. A secular India accepted the apex court’s verdict with calm and grace.

A five-member bench led by Chief Justice Ranjan Gogoi and comprising Justice Sharad Arvind Bobde, Justice Ashok Bhushan, Justice S. Abdul Nazeer and Justice D.Y. Chandrachud directed the Center to form within three months a trust which will build a temple at the disputed site.

The Sunni Waqf Board, which was a party to the seven-decade-old title suit, should be given an alternate five-acre land at some other suitable place for construction of a mosque, the bench said in a unanimous judgement.

The Babri Masjid was a mosque in Ayodhya, India, at a site believed by Hindus to be the birthplace of Lord Rama. It has been a focus of dispute between the Hindu and Muslim communities since the 18th century. According to the mosque’s inscriptions, it was built in 1528–29 by general Mir Baqi on orders of the first Mughal emperor Babur. The mosque was attacked and demolished by Karsevaks in 1992 and ignited communal violence across the country.

The mosque was located on a hill known as Ramkot. According to Hindus, Baqi destroyed a pre-existing temple of Rama at the site. The existence of the temple itself is a matter of controversy. In 2003, a report by the Archaeological Survey of India suggested that there appears to have existed an old structure at the site.

Baqi Tashqandi, also known as Mir Baqi or Mir Banki, was a Mughal commander originally from Tashkent (in modern Uzbekistan) during the reign of Babur. Babur, born Zahir ud-Din Muhammad, was the founder and first emperor of the Mughal dynasty in the Indian subcontinent. He was a direct descendant of Emperor Timur (Tamerlane) of Uzbekistan.

But the fact of the matter is that Babri Majid is only just one example of Muslim invaders destroying Hindu, Jain and Buddhist temples in the Indian subcontinent and beyond. Take the case of the Qutab Minar, a five-story minaret in Mehrauli area of India’s capital Delhi which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Within the Qutab complex is the Quwwat-ul-Islam mosque. It was the first mosque built in Delhi after the Islamic conquest of India and the oldest surviving example of Ghurids architecture in Indian subcontinent. The construction of this Jami Masjid (Friday Mosque) was started in the year 1193 AD by Qutubuddin Aibak, founder of the Slave Dynasty. The site of the mosque was the heart of the captured Rajput citadel of Qila Rai Pithora.

Of the site selected by Aibak for the construction of a mosque, Ibn Battuta, the 14th-century Arab traveller, says, before the taking of Delhi it had been a Jain temple, which the Jains called elbut-khana, but after that event it was used as a mosque. The Archaeological Survey of India states that the mosque was raised over the remains of a temple and, in addition, it was also constructed from materials taken from other demolished temples, a fact recorded on the main eastern entrance. According to a Persian inscription still on the inner eastern gateway, the mosque was built with parts taken from of 27 destroyed Jain temples that were built previously during the reigns of the Tomaras and Prithviraj Chauhan.

Then take the case of the Kashi Vishwanath temple in Varanasi. It was demolished by Aurangzeb, the sixth Mughal emperor, who constructed the Gyanvapi Mosque atop the original Hindu temple. Kashi Vishwanath was among the most renowned Hindu temples of India. Even today, the pillars and the structure of the original temple can be clearly seen.

Aurangzeb’s demolition of the temple was motivated by the rebellion of local zamindars (landowners) associated with the temple. The temple’s demolition was intended as a warning to the anti-Mughal factions and Hindu religious leaders in the city.

Then again, the Alamgir Mosque in Varanasi was constructed by Aurnagzeb atop the ancient 100-ft high Bindu Madhav (Nand Madho) temple after its destruction in 1682.

The plunder by Muslim invaders in India was not limited to places of worship alone. It extended to educational institutes too. The Nalanda University is an example. The decline of Nalanda is concomitant with the disappearance of Buddhism in India.

In around 1193 CE, Muhammad bin Bakhtiyar Khalji, a Turkic chieftain out to make a name for himself, was in the service of a commander in Awadh. The Persian historian, Minhaj-i-Siraj in his Tabaqat-i Nasiri, recorded his deeds a few decades later. Khalji was assigned two villages on the border of Bihar which had become a political no-man’s land. Sensing an opportunity, he began a series of plundering raids into Bihar and was recognized and rewarded for his efforts by his superiors. Emboldened, Khalji decided to attack a fort in Bihar and was able to successfully capture it, looting it of a great booty.

Minhaj-i-Siraj wrote of this attack: “Muhammad-i-Bakht-yar, by the force of his intrepidity, threw himself into the postern of the gateway of the place, and they captured the fortress, and acquired great booty. The greater number of the inhabitants of that place were Brahmans, and the whole of those Brahmans had their heads shaven; and they were all slain. There were a great number of books there; and, when all these books came under the observation of the Musalmans, they summoned a number of Hindus that they might give them information respecting the import of those books; but the whole of the Hindus had been killed. On becoming acquainted (with the contents of those books), it was found that the whole of that fortress and city was a college, and in the Hindui tongue, they call a college Bihar.”

This passage refers to an attack on a Buddhist monastery (the “Bihar” or Vihara) and its monks (the shaved Brahmans). The exact date of this event is not known with scholarly estimates ranging from 1197 to 1206. While many historians believe that this monastery which was mistaken for a fort was Odantapura, some are of the opinion that it was Nalanda itself. However, considering that these two Mahaviharas were only a few kilometers apart, both very likely befell a similar fate. The other great Mahaviharas of the age such as Vikramshila and later, Jagaddala, also met their ends at the hands of the Turks at around the same time.

Another important account of the times is the biography of the Tibetan monk-pilgrim, Dharmasvamin, who journeyed to India between 1234 and 1236. When he visited Nalanda in 1235, he found it still surviving, but a ghost of its past existence. Most of the buildings had been damaged by the Muslims and had since fallen into disrepair. But two viharas, which he named Dhanaba and Ghunaba, were still in serviceable condition with a 90-year-old teacher named Rahula Shribhadra instructing a class of about 70 students on the premises. Dharmasvamin believed that the Mahavihara had not been completely destroyed for superstitious reasons as one of the soldiers who had participated in the desecration of a Jnananatha temple in the complex had immediately fallen ill.

And the plunder by the Muslim invaders went beyond the Indian subcontinent. The Menara Kudus Mosque or Al-Aqsha Mosque located in Kudus in the Indonesian province of Central Java is such an example. Dating from 1549, it is one of the oldest mosques in Indonesia, built at the time of Islam’s spread through Java. The mosque preserves the tomb of Sunan Kudus, one of the nine Islamic saints of Java, and it is a popular pilgrimage point.

The mosque preserves pre-Islamic architectural forms such as old Javanese split doorways, ancient Hindu-Buddhist influenced Majapahit-style red brickwork, and a three-tired pyramidal roof. The most unusual feature is the brick minaret on which a pavilion shelters a large skin drum (bedug) which is used to summon the faithful to prayer instead of the more common muezzin. Whereas a bedug normally hangs under the eaves of a mosque verandah, in the Kudus Mosque it sits in a tower like a Balinese Hindu temple kul-kul or signal drum used to warn of impending attack, fire, or communal event. No other mosque in Java is known to have a drum tower of this type.

In front of the minaret and around the compound are walls and gateways in the old candi bentar (split gate) and kori agung (main gate) styles. Inside are two gateways – a smaller, inner gate with relief panels on either side similar to those found in Mantingan, and an outer gate that is reminiscent of the 14th-century Bajang Ratu gate at Trowulan. Other pre-Islamic touches include eight kala-head water spouts in the ablution area and Ming procelain plates set in the walls.

The pre-Islamic elements suggest the complex has incorporated a pre-existing Hindu-Javanese structure. Th

e mosque has been rebuilt several times removing evidence of what the original structure looked like.

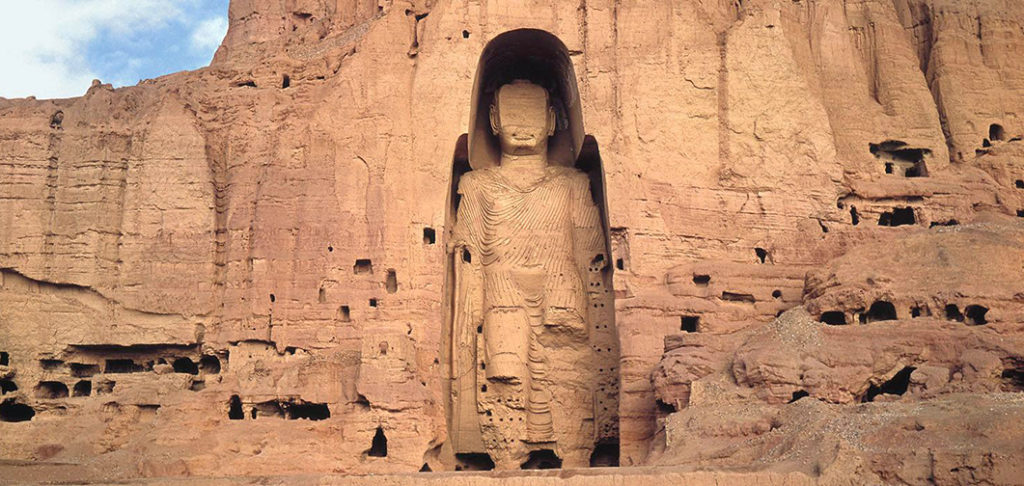

In modern times too, the plunder of iconoclastic religious symbols continued, the most famous example of which are the Bamiyan Buddhas of Afghanistan. The Buddhas of Bamiyan were two sixth century monumental statues of Gautama Buddha carved into the side of a cliff in the Bamiyan valley in the Hazarajat region of central Afghanistan, 230 km northwest of Kabul at an elevation of 2,500 meters. Built in 507 CE (smaller) and 554 CE (larger), the statues represented the classic blended style of Gandhara art. They were respectively 35 m and 53 m tall.

The statues were dynamited and destroyed in March 2001 by the Taliban, on orders from leader Mullah Mohammed Omar, after the Taliban government declared that they were idols. An envoy visiting the United States in the following weeks said that they were destroyed in protest of international aid exclusively reserved for statue maintenance while Afghanistan was experiencing famine. The Afghan Taliban Foreign Minister claimed that the destruction was merely about carrying out Islamic religious iconoclasm. International opinion strongly condemned the destruction of the Buddhas.

In April 2002, Afghanistan’s post-Taliban leader Hamid Karzai called the destruction a “national tragedy” and pledged the Buddhas to be rebuilt. He later called the reconstruction a “cultural imperative”.

In September 2005, Mawlawi Mohammed Islam Mohammadi, Taliban governor of Bamiyan province at the time of the destruction and widely seen as responsible for its occurrence, was elected to the Afghan Parliament. He blamed the decision to destroy the Buddhas on Al Qaeda’s influence on the Taliban. In January 2007, he was assassinated in Kabul.

Since 2002, international funding has supported recovery and stabilization efforts at the site. Fragments of the statues are documented and stored with special attention given to securing the structure of the statue still in place. It is hoped that, in the future, partial anastylosis can be conducted with the remaining fragments. In 2009, the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) constructed scaffolding within the niche to further conservation and stabilization. Nonetheless, several serious conservation and safety issues exist and the Buddhas are still listed as World Heritage in Danger.

The Buddhist remnants at Bamiyan were included on the 2008 World Monuments Watch List of the 100 Most Endangered Sites by the World Monuments Fund.

In 2013, the foot section of the smaller Buddha was rebuilt with iron rods, bricks and concrete by the German branch of ICOMOS. Further constructions were halted by order of UNESCO, on the grounds that the work was conducted without the organization’s knowledge or approval. The effort was contrary to UNESCO’s policy of using original material for reconstructions, and it has been pointed out that it was done based on assumptions.

After the destruction of the Buddhas, 50 caves were revealed. In 12 of the caves, wall paintings were discovered. In December 2004, an international team of researchers stated the wall paintings at Bamiyan were painted between the 5th and the 9th centuries, rather than between 6th and 8th centuries, citing their analysis of radioactive isotopes contained in straw fibers found beneath the paintings. It is believed that the paintings were done by artists travelling on the Silk Road, the trade route between China and the West.

Scientists from the Tokyo Research Institute for Cultural Properties in Japan, the Centre of Research and Restoration of the French Museums in France, the Getty Conservation Institute in the United States, and the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in Grenoble, France, analyzed samples from the paintings, typically less than 1 mm across. They discovered that the paint contained pigments such as vermilion (red mercury sulfide) and lead white (lead carbonate). These were mixed with a range of binders, including natural resins, gums (possibly animal skin glue or egg), and oils, probably derived from walnuts or poppies. Specifically, researchers identified drying oils from murals showing Buddhas in vermilion robes sitting cross-legged amid palm leaves and mythical creatures as being painted in the middle of the 7th century. It is believed that they are the oldest known surviving examples of oil painting, possibly predating oil painting in Europe by as much as six centuries. The discovery may lead to a reassessment of works in ancient ruins in India, Iran, China, Pakistan, and Turkey.

Despite its people being butchered or converted to other religions and places of worship destroyed over the centuries, India has been the land that has given asylum to people who have faced religious persecution in other parts of the world, including Jews, Christians, Zoroastrians, Buddhists and followers of various schools of Islam. In fact, India is the land where secularism is manifested best.