MASSACHUSETTS: Hospitals can now treat people having low risk thyroid cancer with a smaller amount of radioactivity after surgery, according to a latest study.

MASSACHUSETTS: Hospitals can now treat people having low risk thyroid cancer with a smaller amount of radioactivity after surgery, according to a latest study.

Billed as the world’s longest-running trial of low risk thyroid cancer patients carried out in the UK, the suggested guidelines, when accepted, are likely to benefit thousands of people.

Dr Jonathan Wadsley, a consultant clinical oncologist at the Weston Park Hospital at Sheffield, and chair of the National Cancer Research Institute (NCRI) Thyroid Cancer Subgroup, presented the results at the recently-held 2018 NCRI Cancer Conference in Glasgow.

The latest results showed that there was no significant difference in the recurrence of cancer rate between patients given a low radiation dose compared to the standard, higher dose.

When patients received lower activity, they suffered fewer side effects. They faced less risk of feeling sick or suffering damage to the salivary glands, which can potentially lead to a permanently dry mouth, the study found.

Reduced dose reduces the patients’ chance of getting cancer later, it said.

According to experts, many patients find it distressing to remain in isolation rooms in the hospital for two to three days without physical contact with friends and relatives when they receive higher doses.

When applied doses are high, radiation protection regulations demand that the dose should come down before releasing the patient from the isolation room. Health services save money when patients receive low activity. Besides this, hospitals can treat more patients.

Radiation protection enthusiasts endorse for patient’s treatment an amount of radioactivity as low as reasonably achievable without sacrificing clinical benefits.

Researchers at AIIMS, New Delhi, are seen as pioneers in this field. In 1996, AIIMS researchers carried out the first prospective randomised clinical trial with regard to administered dose for destroying remnant cells.

Apart from their study, other two studies were from France (ESTIMABL group) and, the UK (HiLo study).

The latter two had longer follow up. Though physicians used radioiodine for treatment of thyroid cancer for several decades, it continued to be an enigma.

In 2014, in a clinical review of low risk thyroid cancer published in the British Medical Journal, researchers noted that thyroid cancer is one of the fastest growing diagnoses, more cases of thyroid cancer are found every year than all leukemias, and cancers of the liver, pancreas and stomach. They found that most of these incident cases are papillary in origin and are both small and localized.

“Patients with these small localized papillary thyroid cancers have a 99 per cent survival rate at 20 years. In view of the excellent prognosis of these tumors, they have been denoted as low risk. The incidence of these low risk thyroid cancers is growing probably because of the use of imaging technologies capable of exposing a large reservoir of sub clinical disease” they clarified.

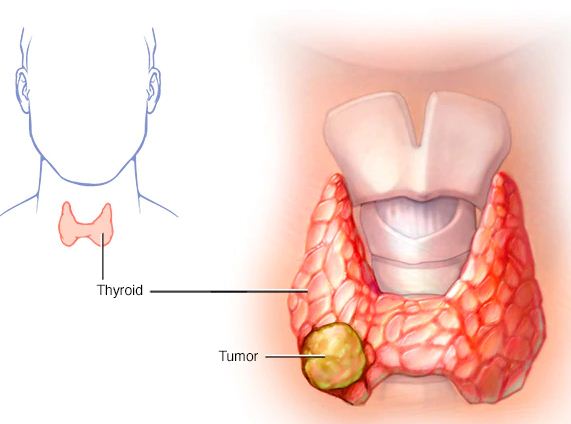

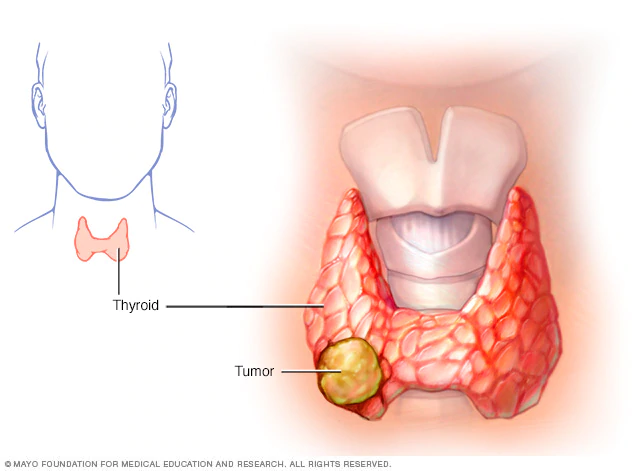

The first step in treating thyroid cancer is to remove the thyroid surgically. Even an experienced surgeon may leave some cancer cells and thyroid cells at the site. Some cells may move away. The physicians want to destroy any residual normal thyroid tissue and thyroid cancer cells following surgery. If physicians do not do this, the remnant cells may proliferate, leading to recurrence of cancer later.

The cancer specialists administer radioactive iodine (I-131) in liquid or capsule form to avoid this. The radioisotope concentrates in thyroid cells in the body wherever they are. Radiation emitted from radioiodine destroys the remnant thyroid cells left after surgery.

Dr Wadsley reported results of 434 patients with low risk thyroid cancer from 29 UK hospitals in the HiLo trial with a median (average) follow-up time of 6.5 years.

He confirmed to this writer that many UK centers have already adopted the low dose regimen to treat low risk thyroid cancer patients, following the publication of the primary outcome of the study back in 2012.

“The recently reported longer term follow up data gives us added confidence that use of the lower dose regimen does not lead to an increase in longer term thyroid cancer recurrence,” he asserted.

The Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology has accepted the study for publication; it is currently undergoing final editorial review.

According to Dr Martin Forster from University College London, who chairs the NCRI Head and Neck Clinical Studies Group but was not involved with this research, “Nearly seven years of follow-up data from the HiLo trial provide us with confidence that the lower radiation dose for patients with low risk thyroid cancer is a safe and effective treatment, and that international guidelines can be updated to reflect this. For many patients, the treatment and how it is delivered, as well as the short and long-term side effects, can have a big impact on their lives.” PTI