Sunthar-Visuvalingam

Sunthar-Visuvalingam

CHICAGO: An unusual summer exhibition featuring ten Indian artists drew a crowd for its opening July 6 at downtown Loyola University Museum of Art (LUMA). Each was responding imaginatively from their Indian perspectives, to selections from a collection of 127 B&W WWII photos taken in 1945 by a still unknown American airman stationed in Bengal.

Having found them in a shoebox at a sale in Northbrook, Illinois, curators Alan Teller and Jerri Zbiral became obsessed with tracing the identity, whereabouts and motivations of the mystery photographer, and made several trips to India to explore the origins, implications and local resonances of these evocative images of yesteryear.

For their 90-minute guided tour the following afternoon,attended by a rapt but largely non-Desi audience, the married couple was joined by Prof. Chhatrapati Dutta, Director of Kolkata’s Government College of Art & Craft, who added insightful personal and technical details on the local background of each artist and their works.

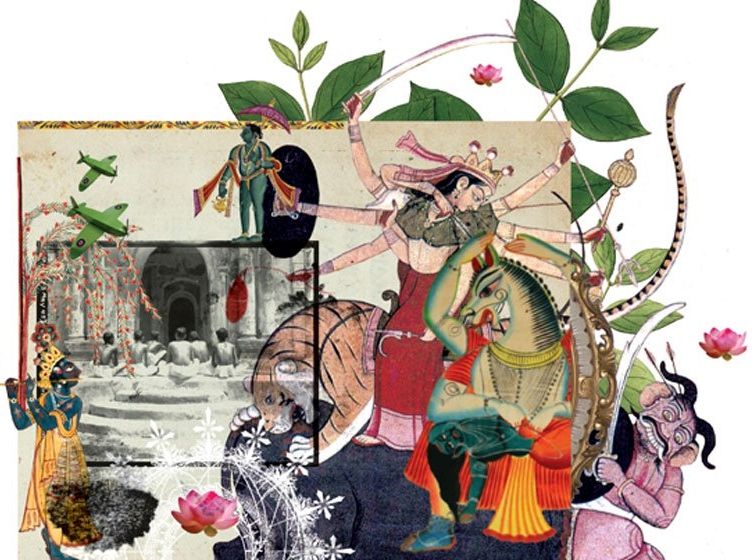

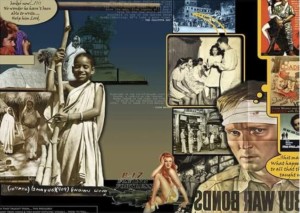

Even where seemingly irrelevant, a ubiquitous image across several contributing artists, are (American) warplanes streaking across the Indian skies. The very first gallery employs the traditional motif of the “wish-fulfilling tree-of-life” towering over Bengal, but with death alone as its only fruit, strikingly depicted by an animal skeleton surrounded by nationalistic flags. Whereas the photos capture portraits, habitations and scenes through an empathetic if alien lens, Dutta explained how his own gallery seeks to resituate these ‘innocent’ memories in their immediate global context of empire, world war, propaganda and ethnocide.

The US Airforce was based in Bengal to face an expected Japanese invasion from Burma. By hoarding and exporting grain to other war-theaters and shutting down boat transportation to deny nourishment to the eventual invaders, the colonial administration created “the largest artificial famine in history” that took the lives of perhaps more than four million natives. British Premier Winston Churchill disregarded urgent pleas to divert ships bearing precious grain from Australia, etc that were sailing past the Bengal coastline.

The way local color, beliefs, attitudes have been invested into these otherwise lifeless photos is exemplified by their incorporation by two women into traditional scrolls (patua). One, who has transformed their subject matter into authentic folk-art, is even seen (on video) narrating their stories in Bengali song. It was a derelict temple that betrayed the photographer’s whereabouts.

Overwhelmed by the photo, its present priest incorporated the curators’ names into his incantation. Keen to gain admittance into a temple-sanctum, they have cleverly allowed American visitors to relive that situation.

Two of the artists insist on restoring the identity of the mystery photographer. One produces a ‘documentary’ that reveals him to be of Jewish origin writing back to his fiancée in Baltimore. The other, having ferreted him out in the American heartlands, becomes so identified with the artistic quest that he flies to Japan to determine how this “Miller” finally ended his life!

Commenting on the last series of paintings, Teller singled out how the “graphic novelist” reverses the optical relation between photographer and subject, with the latter perceiving the former upside-down. Beyond its undeniable artistic merits and originalities, what this “Following the Box” exhibition really facilitates is a multifaceted dialogue, across time and space, between that empathetic and enduring (camera) gaze and its contemporary Indian subjects. Outside of the joint war-effort, ‘freedom-loving’ Americans were at that time not welcome in British India, because the colonial administration feared their natural sympathies for the independence struggle.

The last question posed was whether the guides had taken the trouble to speak to American veterans from the Indian theater to determine the photographer’s identity. Zbiral’s own “shadow boxes” exhibit visually maps, at the start of our tour, their entire project as a series of interlocking boxes corresponding to seven interrogations beginning with what, where, how, etc. The last two, why and who, remain detached from the remaining bloc, with “who” remaining pitch black. But more important than the individual behind the camera is this ‘pre-anthropological’ gaze that does not exoticize, or even comment, but remains attentive and attuned to the truth of its subject.

Such an empathetic gaze remains alive here and now in 94-year-old professor McKim Marriott, who was originally trained to decipher Japanese coded messages and posted to India. He not only started taking similar photos, first while cycling around Delhi, but came back to study then teachanthropology at the University of Chicago. Marriot remained true to his intellectual vocation of letting the Indians speak of themselves through their own traditional categories of understanding, just as our curators “Following the Box” have, in their own way, ended up reversing the American lens.

The exhibition, which continues through October 20, will feature several related events. An amateur video recording of the entire guided tour is available Here